Items related to A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival...

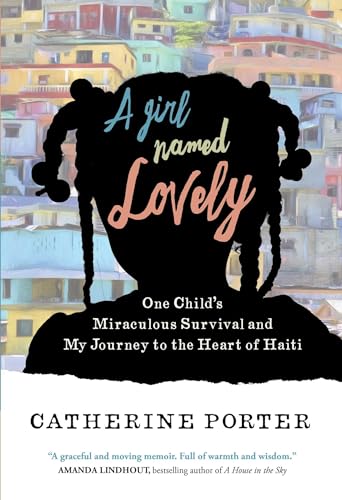

A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti - Softcover

In January 2010, a devastating earthquake struck Haiti, killing hundreds of thousands of people and paralyzing the country. Catherine Porter, a newly minted international reporter, was on the ground in the immediate aftermath. Moments after she arrived in Haiti, Catherine found her first story. A ragtag group of volunteers told her about a “miracle child”—a two-year-old girl who had survived six days under the rubble and emerged virtually unscathed.

Catherine found the girl the next day. Her family was a mystery; her future uncertain. Her name was Lovely. She seemed a symbol of Haiti—both hopeful and despairing.

When Catherine learned that Lovely had been reunited with her family, she did what any journalist would do and followed the story. The cardinal rule of journalism is to remain objective and not become personally involved in the stories you report. But Catherine broke that rule on the last day of her second trip to Haiti. That day, Catherine made the simple decision to enroll Lovely in school, and to pay for it with money she and her readers donated.

Over the next five years, Catherine would visit Lovely and her family seventeen times, while also reporting on the country’s struggles to harness the international rush of aid. Each trip, Catherine's relationship with Lovely and her family became more involved and more complicated. Trying to balance her instincts as a mother and a journalist, and increasingly conscious of the costs involved, Catherine found herself struggling to align her worldview with the realities of Haiti after the earthquake. Although her dual roles as donor and journalist were constantly at odds, as one piled up expectations and the other documented failures, a third role had emerged and quietly become the most important: that of a friend.

A Girl Named Lovely is about the reverberations of a single decision—in Lovely’s life and in Catherine’s. It recounts a journalist’s voyage into the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, hit by the greatest natural disaster in modern history, and the fraught, messy realities of international aid. It is about hope, kindness, heartbreak, and the modest but meaningful difference one person can make.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

It felt like the plane was landing in the middle of the ocean.

Peering out a window, I could see nothing but vast blackness. There were no white lights dotting the edges of the runway, no brightly lit terminal buildings in the distance, and, beyond that, no twinkling city lights. Just blackness, then bump: we were on the ground.

But the voice over the plane’s loudspeaker confirmed that we had in fact arrived at our destination: the devastated city of Port-au-Prince.

It was 10:00 p.m. on January 23, 2010, eleven days after the earthquake. Somewhere out there in the darkness were hundreds of thousands of bloated corpses, severely injured people, and armed thugs who were using the chaos to loot, rape, and exact hideous revenge by burning their enemies alive in the streets. I’d seen pictures of the latter, taken by my colleague, photographer Lucas Oleniuk, and splayed across the front page of our newspaper, the Toronto Star. They had kept me awake for the past couple of nights, ever since my editor had phoned me during lunch and asked if I wanted to go to Haiti.

“Of course,” I’d said without pause. I was a columnist at the newspaper, but my dream was to become a foreign correspondent. This was my big break. But I’d been quietly freaking out since that moment. What if I was kidnapped by one of those thugs? What if I witnessed a public lynching? Would I be able to handle the Civil War–era amputations to remove gangrenous limbs that my colleagues had reported were taking place in tents around the city?

I packed in our basement the night before my planned departure as my two little kids looked on from the couch. This would be my longest separation from them. Was I being an irresponsible parent, leaving them to travel into danger? Would I return injured or broken? But if I didn’t go, how could I ever forgive myself? Most days, I felt emotionally stretched between two worlds as a working mom; now that tug-of-war between ambition and duty felt as though it would snap me in half. When I couldn’t find my freshly purchased Lonely Planet guide to the Dominican Republic and Haiti, I started frantically tearing apart my bag and sobbing uncontrollably. I was having a full-fledged panic attack. My kids cuddled me on the couch and recited the soothing words I always told them: “Everything will be okay, Mommy.”

Adding to the sticky fear that clenched my stomach and muffled my lungs was performance anxiety. Every journalist is crippled by self-doubt most of the time. We all think we’ve somehow managed to patch things together thus far, but that it’s only a matter of time before everyone else figures out that we are winging it. Would this be the trip that revealed all my failings? Would I crack under the pressure and be forced to call my editor blubbering and begging to be brought home? Would I get scooped by all the competing journalists and miss the big stories?

A cheer went up in the plane around me. I was at the back of an Air Canada relief flight, surrounded by mostly female airline staff who had been trained as caregivers to soothe survivors after airplane “incidents”—scares or, worse, crashes. For them, this trip was about delivering aid to their colleagues in Haiti and bringing Haitian orphans, whose international adoptions had been expedited by the Canadian government, back to their new homes in Canada.

The volunteers wore matching beige T-shirts with the word “Hope” printed in English, French, and Kreyòl ayisyen —Haitian Creole, one of the country’s two official languages—on the back. They had spent most of the ride bouncing excitedly between seats, snapping photos of one another and passing out chocolates and home-baked muffins.

“What we are doing is greater than all of us,” their upbeat leader, Duncan Dee, had announced over the plane’s loudspeaker before takeoff.

Duncan was the chief operating officer for Air Canada, which had become Canada’s official emergency aid transporter after the Southeast Asian tsunami four years earlier. He was short, with cropped black hair and glasses that amplified his round face. This was his third aid mission, after Indonesia and Hurricane Katrina, and already it had a special significance.

A few nights before, Duncan had watched a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) newscast from Port-au-Prince featuring a child getting sutures without anesthetic at a bare-bones medical clinic. The child’s screams moved Duncan to tears and haunted him. He was a devout Catholic with two children of his own.

“I couldn’t not do anything, knowing I would be in Port-au-Prince forty-eight hours after that child was screaming,” he said. He’d picked up his phone and emailed Peter Mansbridge, the anchor of the flagship CBC newscast The National, who directed him to a reporter in Port-au-Prince. Within an hour Duncan had connected with a volunteer at the makeshift clinic who provided a long list of needed supplies.

Over the past two days Duncan and his volunteer crew had crisscrossed Ottawa, personally collecting wheelchairs, generators, and diapers. Except for one type of antibiotic, they had picked up every last thing on the list. They were high on compassion and buzzing from the endorphins of altruism.

“It’s a privilege for us to do this. We are helping people who have nothing,” Duncan said.

Back in economy class, I and my colleague Brett Popplewell, a reporter with the Star, were the only ones who were getting off. We weren’t here to save lives or help in any tangible way. We were here to witness whatever horrors were unfurling in the darkness and report it to our readers back in Canada.

I nervously checked my bag one more time to make sure I had everything: my pens and notebooks, camera and laptop. I tapped my waist, where I was wearing a money belt filled with my passport and a thick wad of American dollars I’d packed to pay for drivers, translators, and a hotel room, if I could find one.

I began to shuffle my way to the airplane exit, a sense of dread growing with each step. My breath was shallow, and nausea gripped my stomach. As I was leaving, the Air Canada agent who’d been the most buoyant and enthusiastic called out to me: “Good luck.”

· · ·

Outside, the air was thick and warm, like a damp wool blanket. The smell of burning rubber filled my nostrils. It was dark except for the headlights of a giant pickup truck that had rolled right up to the plane, and the white glow of a television camera.

From atop the metal staircase, I could see Duncan’s round face illuminated in the camera’s glare below. The same CBC reporter who had inspired him to help was now interviewing him.

A knot of people moved in the shadows nearby. When I reached the ground, I quickly learned most had arrived to pick up the emergency supplies Air Canada staff had carefully collected.

These weren’t professional aid workers, though. They seemed to be just a bunch of random people who, like Duncan, had watched the news and been inspired to help Haiti in person. I would come to call them catastrophe missionaries.

“We’ve been setting up tents, holding babies, seeing a woman give birth,” said a thirty-year-old man from New Jersey wearing a baseball cap and baggy shorts. “It’s been the craziest two days. We rode in on the back of a dump truck to get here. We brought bags of lollipops to give to kids. We were jumping rope with them today.”

When I asked him his job, he said his fiance was in medical school. I raised my eyebrows. Seriously, what good did he think he was doing skipping with kids in an earthquake zone? I at least had a job to do here. He was just some yahoo who’d come for a strange thrill. I figured he would cause more harm than good. But I scratched everything he told me down in my notebook, hoping my pen was working in the dark. The best cure for performance anxiety is action, and interviewing someone—anyone—was calming.

The man pointed out his group’s leader, a tall, slim, and slow-talking information technology specialist from Manhattan named Alphonse Edouard. Alphonse had been vacationing in the Dominican Republic when the earthquake struck and had rushed over the border with two duffel bags of hastily purchased medical supplies. He’d met up with members of the Dominican Republic Civil Defense and some Greek doctors, and together they’d set up a medical clinic on the edge of an industrial complex near the airport. It was Alphonse who had sent Duncan the list of needed supplies.

“I’m still pinching myself. I can’t believe the plane is actually here,” Alphonse said. “The people of Haiti really need the relief.”

At the clinic, doctors were seeing dozens of patients a day, treating fractures and delivering babies. As I scrawled down his words, I heard something that made me stop. His clinic was taking care of a “miracle baby,” a little girl named Jonatha who had been dropped off six days after the earthquake. The girl had survived all six days under the rubble alone. He figured she was one and a half years old.

“We’ll have to do something for her,” he said. “Her parents died.”

Six days without water—that seemed a miracle indeed, particularly for such a small person. My kids, Lyla and Noah, were three and one, and they wouldn’t make it a single day without food or water. Even when we were stepping out for a quick errand, I packed as though we were going on a two-day canoe trip with an assortment of snacks in various containers and multiple brimming sippy cups.

I had to find this girl. Alphonse directed me to something called “Sonapi.”

“Go to the Trois Mains and turn right,” he said. I had never been to Haiti before, so the directions meant nothing to me, but I figured locals would know what he was talking about and lead me there.

As we were talking, boxes were being off-loaded from the plane onto the warm tarmac. I spotted my bulky camping knapsack among them. I hauled my bag up onto my back and asked an Air Canada employee if she could tell me the direction of the hangar. She stretched out her finger and pointed under the plane.

With Brett beside me, we shuffled under the hulking belly of the giant Airbus A330 in the direction the airline employee had indicated, hoping that we’d bump into the hangar. We were immediately enveloped by the darkness. I couldn’t see a thing. I was still scared, but there was a slight loosening of the coils in my stomach. In a few hours I was going to head out and find that orphaned girl, wherever she was.

· · ·

When the sun rose the next morning, the view was devastating.

Port-au-Prince was built around valleys that had once been verdant with trees. At first glance, it also seemed that there were waterfalls flowing down the hills around the city. A closer look revealed that the white wasn’t spray but concrete blocks that had spilled down the valley, one small house smashing the next.

Jumbled piles of concrete lined both sides of the street. The buildings were flattened, tipped over, reduced to skeletons of rebar and wood. Some offered clues to their former lives: a Yamaha sign resting atop a mess of rubble, a large wooden cross with Jesus rising before a jumble of bricks and broken stained glass windows.

So many of the buildings were broken that the ones left standing were easy to spot. They stood out. They resembled dissected carcasses. Here I could see the rows of dusty desks up on the third floor of a sliced-open building, and there the baby bassinets of a medical clinic.

We passed the country’s largest cathedral, called locally the Port-au-Prince Cathedral, which now resembled a Roman ruin: no roof or stained glass, just pillars and bare walls. And there were the three white domes of the presidential palace. The central one had collapsed like a sunken marzipan cake.

A vast camp spread around the palace in what had once been the city’s version of Central Park and Times Square combined—a dozen small parks dotted with graceful trees and statues of revolutionary heroes. Before, this was where locals would meet at the end of the day to eat ice cream or do their homework beneath the streetlamps. During the annual carnival, it was where the parade and dancing took place. Now every inch of ground was clogged by homemade tents fashioned from bedsheets. I could make out a children’s play structure, with a slide and a ladder in the distance. People had camped out on its upper platform, where kids were meant to line up for their turn down the slide.

People lay on the streets all around, under sheets or tied-up tarps. Others rummaged through the rubble, heaving hammers and digging with their bare hands. Signs made with spray paint flashed from walls and hanging sheets: We need food. Water Please. S.O.S. We need help. We need help. We need help.

I scrawled down notes as I toured the city, trying to get my bearings. But just as I fixed my eyes on one broken thing, another leapt into view. I felt like a kid in a haunted house, overwhelmed and distracted. It was too much to take in.

Brett and I were the second team of reporters from our newspaper to arrive, relieving our colleagues who had rushed into the country a couple of days after the quake and were now strung out and exhausted. They had already reported on the death and destruction. Our assignment was to document what came next: the aid and presumably, the first steps of healing.

But the devastation was so overpowering, it was hard to imagine moving on from it. How could anyone heal from this type of damage?

We stopped in at a police station near the airport, which had become the Haitian government’s temporary headquarters, since most ministry buildings had collapsed. The only sign of any government, though, was the long-faced communications minister, Marie-Laurence Jocelyn Lassègue, sitting alone at a table under a dusty mango tree. A piece of paper had been folded to make a nameplate in front of her, with the word Presse.

“We need tents, medicines, nurses,” she said forcefully in perfect English. It was as if I’d pushed the play button on her monologue, and she rushed on without breaking or even breathing. “The NGOs don’t look at the government’s priority, and they need to be better coordinated. The majority of the population is women and they lost everything. It was already very hard for them to live. It seems the jail was opened, and there have been many rapes. We need soldiers to protect them and put lights up in the camps.”

When I left the station, I was immediately swept up in the next matter; it was all I could do to keep up. But I would soon learn just how prescient Minister Lassègue’s words were.

All morning, I had been emailing Alphonse, the volunteer coordinator, trying to get better directions to the clinic where the miracle girl was being cared for. He had repeated the same two things: “Sonapi” and “Trois Mains.”

Even before the earthquake, Port-au-Prince was an easy city to get lost in. Few of the warren-like streets had names, let alone signs. To find their way, locals used landmarks to give directions: Go to this supermarket, say, turn left, and when you get to the big house with three satellite dishes, turn right. But most of the usual landmarks were now gone, so even locals could spend hours trying to find their way around town.

When I asked our driver if he knew “Sonapi” or “Tr...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster

- Publication date2019

- ISBN 10 1501168096

- ISBN 13 9781501168093

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. New Condition, Paperback book, Seller Inventory # 2309080109

Girl Named Lovely : One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 34937304-n

A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti by Porter, Catherine [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9781501168093

A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 1501168096-2-1

A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-1501168096-new

A Girl Named Lovely Format: Hardback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 9781501168093

A Girl Named Lovely (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. An insightful and uplifting memoir about a young Haitian girl in post-earthquake Haiti, and the profound, life-changing effect she had on one journalist's life. In January 2010, a devastating earthquake struck Haiti, killing hundreds of thousands of people and paralyzing the country. Catherine Porter, a newly minted international reporter, was on the ground in the immediate aftermath. Moments after she arrived in Haiti, Catherine found her first story. A ragtag group of volunteers told her about a "miracle child"--a two-year-old girl who had survived six days under the rubble and emerged virtually unscathed. Catherine found the girl the next day. Her family was a mystery; her future uncertain. Her name was Lovely. She seemed a symbol of Haiti--both hopeful and despairing. When Catherine learned that Lovely had been reunited with her family, she did what any journalist would do and followed the story. The cardinal rule of journalism is to remain objective and not become personally involved in the stories you report. But Catherine broke that rule on the last day of her second trip to Haiti. That day, Catherine made the simple decision to enroll Lovely in school, and to pay for it with money she and her readers donated. Over the next five years, Catherine would visit Lovely and her family seventeen times, while also reporting on the country's struggles to harness the international rush of aid. Each trip, Catherine's relationship with Lovely and her family became more involved and more complicated. Trying to balance her instincts as a mother and a journalist, and increasingly conscious of the costs involved, Catherine found herself struggling to align her worldview with the realities of Haiti after the earthquake. Although her dual roles as donor and journalist were constantly at odds, as one piled up expectations and the other documented failures, a third role had emerged and quietly become the most important: that of a friend. A Girl Named Lovely is about the reverberations of a single decision--in Lovely's life and in Catherine's. It recounts a journalist's voyage into the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, hit by the greatest natural disaster in modern history, and the fraught, messy realities of international aid. It is about hope, kindness, heartbreak, and the modest but meaningful difference one person can make. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781501168093

A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1501168096

A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1501168096

A Girl Named Lovely: One Child's Miraculous Survival and My Journey to the Heart of Haiti

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1501168096