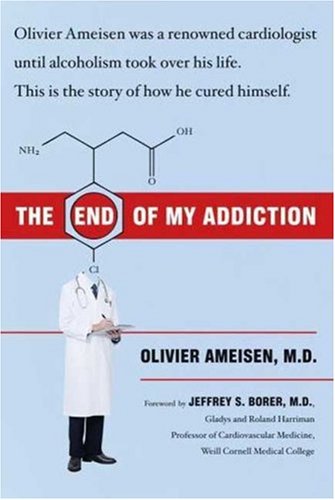

Items related to The End of My Addiction

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

1. Moment of Truth

I CAME TO MY SENSES and took stock of where I was: in a cab, with blood streaming down my face and spattering my trench coat. I looked out the window and in the glow of the streetlights saw the cab was on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, waiting for the light to change at 76th Street. The church on the corner reminded me it was Sunday, and I looked at my watch. It was almost midnight. The few people on the street were buttoned up against the late winter chill, but it was warm in the cab.

My apartment was not too far away, on East 63rd Street between York and First Avenues, but I needed medical attention. I asked the driver to take me to the emergency room at New York Hospital, at 68th Street and York Avenue. He seemed oblivious to my condition, and I wondered what had happened. Had the cab braked suddenly so that I hit my head, or had I been injured in some other way before I hailed it? I knew I’d been drinking, but not where or how much.

As the cab pulled up in front of the hospital emergency room entrance, a memory of the evening began to come together. Around 8:30 p.m. I had visited my friend Jeff Steiner, the CEO of Fairchild Corporation, to ask his advice on running my cardiology practice, which I’d started two and a half years before. I’d been introduced to Jeff in the late 1980s by a mutual friend, another physician.

Although I’d intended not to drink that evening, I felt insulted when Jeff’s butler offered me a choice of teas. "Why doesn’t he offer me an alcoholic drink as well at this hour?" I thought. "Is this a judgmental message?"

I asked for and drank a glass of Scotch, then made a show of declining a refill. Much later I learned that Jeff was not aware that I had been drinking heavily. He’d known me only to have a few drinks at large parties, here and there, over the years. But my mounting concerns about my practice finances had changed that.

The standard expectation is that it will take a new medical practice two years to break even. Mine broke even in four months. And almost three years later, in March 1997, there it remained— hovering a little over the break-even point.

Staggering into the emergency room, I thought, "They will see I’m drunk. That’s not so good. But at least I know the place is well run and will fix me up right." I had been associated with New York Hospital and its partner institution, Cornell University Medical College,* ever since I arrived from France in the fall of 1983 to do research and clinical fellowships in cardiology. Thirteen and a half years later, I was a clinical associate professor

*As the two institutions were then known; in 1998 they became New York-Presbyterian Hospital and Weill Cornell Medical College.

of medicine at Cornell and an associate attending physician at New York Hospital, in addition to running my private practice.

Inside the emergency room, I passed out again. When I came to, one of my ex-students, Matt, now a resident, was standing over me preparing to stitch the wound in my forehead. So as not to be left with a scar, I asked him to use Steri-Strips instead. He did and then left me to lie quietly for a few hours so I could sober up enough to walk home safely. He was plainly even more embarrassed to treat me in my drunken state than I was to need treatment. I cringed at the thought of my appearance in the ER being discussed around the hospital, then pushed the thought out of my mind. Matt was not the kind of person to talk about it; that was some comfort.

Lying there, I ran the video of the evening in my mind. "Run the video of what happens when you drink" was something I’d been hearing in Alcoholics Anonymous, where I was still very much a newcomer.

My conversation with Jeff Steiner had been frustrating for us both. Although he was eager to help, there was a mismatch between his expertise and my problems. What I really needed was a small business adviser, not a big corporate dealmaker.

As I left Jeff’s apartment, my mind whirled with conflicting thoughts. My cost-blind practice style might function better in France’s universal health care system than in the United States, I thought, and I wondered if I should relocate back to Paris, where I was from. But I loved my life in New York. In 1991 I had acquired U.S. citizenship, and it pleased me to be a citizen of a country with so many shared ideals with my country of origin. If not profitable, my practice was at least busy and my work enormously rewarding. My patient roster included wealthy andcelebrated people along with Harlem church ladies on Medicare or Medicaid and the indigent, and I liked that mix. And my social life was wonderfully stimulating—more so than I could imagine having anywhere else. No, I wasn’t eager to leave.

But my practice could not continue indefinitely at this rate, and the constant anxiety created by financial worries was growing into a source of full-blown panic. I struggled with a deep sense of failure, and I lived in fear that the world would see that my accomplishments were nothing but a sham, a house of cards that could collapse at any second.

This was not a new feeling to me. Throughout my life I had been plagued by anxious feelings of inadequacy, of being an impostor on the brink of being unmasked. I had been seeing therapists for a long time before I started drinking. To be honest, they never were much help with my anxiety. Nor was the Xanax they prescribed me.

The one Scotch at Jeff’s made me aware of how thirsty I was. I went to a Chinese restaurant, intending to have a meal as well, but wound up eating nothing and drinking one double vodka after another. And then . . . I found myself bleeding in the taxicab.

It wasn’t my first blackout drinking. But the blackouts were getting more common, whole stretches of evenings expunged from my memory. And this was the first time I’d come out of a blackout with a physical injury. Until then blackouts had only been sources of intense mortification as I wondered what embarrassing things I might have said or done.

The next morning I thought briefly about amusing tales I could concoct to explain the bandages on my forehead. Decidingthat I was too hungover to go to work, I had my office assistant reschedule the day’s patients. As my drinking had increased, I had scrupulously honored my first duty as a doctor—to do no harm. I stopped driving. And I never set foot in my office or the hospital when I was not completely sober.

Still, I resisted seeing myself as a problem drinker. All I really needed, I thought, was to learn to drink better. This delusion was encouraged by a well-meaning friend and an equally well-meaning but I think even more misguided therapist, both of whom undertook to show me how to be a moderate wine drinker rather than a binger on Scotch or vodka. I even began AA with the thought that it might give me tips on managing my drinking better rather than stopping completely.

Not everyone thought I was a candidate for moderation. The two friends who escorted me to my first meeting didn’t think so. One was a longtime AA member, a poet and a writer and a very beautiful woman who looked a bit like Katharine Hepburn. She used to say, "I want you to see me before I lose my looks." She still has those looks today. When we met, she had been sober for many years, yet she told me, "I am an alcoholic." That struck me as very strange, and I was embarrassed to hear her say it. People with diabetes or hypertension didn’t identify themselves by their illnesses. Why should people with alcoholism?

Of course, I thought that because I did not want to admit— to myself or anyone else—that I might be alcohol-dependent. And so I was terrified to go to a meeting. But my friends each took me by an arm, and escorted me from my apartment on East 63rd Street to the major AA meeting place in the neighborhood— the 79th Street Workshop, in the basement of St. Monica’s Catholic Church, on 79th Street between York and First Avenues. Itwas my first step, taken reluctantly, toward facing my illness. But it was a vital one.

It is hard for everyone who attends AA to get past the potential embarrassment of being seen as an alcoholic. Shortly before I went to AA for the first time, my shrink began encouraging me to go. I said, "What about anonymity? My office and my apartment are right in the same neighborhood. What if a patient or somebody else I know sees me?"

He said, "Don’t worry. Anyone inside will be an alcoholic and won’t say anything."

"But what if a colleague sees me entering or leaving the place?"

"It won’t happen."

It did happen. But after I started going to AA, I told him, "AA is a great place. Have you been to a meeting?"

"No."

"You refer people. Maybe you should know what it’s like. Will you come with me to an open meeting?"

"No."

"Why not?"

"Because somebody might see me."

There is a moral stigma to addiction, and it is prospective shame that drives people to resist admitting they have a problem. It leads physicians to miss or delay a diagnosis of addiction, too. Only a couple of months earlier, I had brought up AA in a session with my shrink. "Oh, you’re not an alcoholic," he said dismis-sively, "but you could become one." Then he changed the subject away from alcohol and drinking.

Later on in my alcoholism, when I knew more about the course of the illness, I wondered how he could have missed the signs of its onset in me, and could even have turned a deaf ear to my first outright call for help. The responses of my physician colleagues at New York Hospital–Cornell puzzled me, too. When I would discreetly ask around about how to help "someone" with a drinking problem, they’d ask, "Is the person close to you?"

If I said no, they’d say, "You don’t want to get involved. It’s a minefield."

If yes, "Well, I really don’t know w...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 1616793279

- ISBN 13 9781616793272

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages352

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want