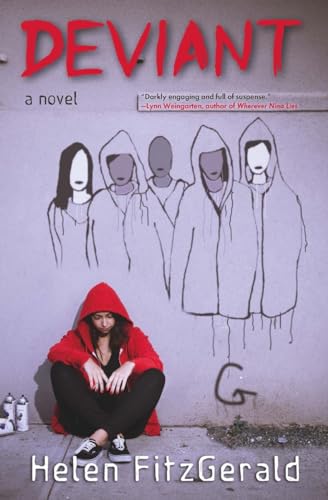

Items related to Deviant

Synopsis

When sixteen-year-old Abigail's mother dies in Scotland—leaving a faded photo, a weirdly cryptic letter, and a one-way ticket to America—she feels nothing. Why should she? Her mother abandoned her as a baby to grow up on an anti-nuclear commune and then in ugly foster homes. But the letter is a surprise in more ways than one: Her father is living in California. What's more, she has an eighteen-year-old sister, Becky. And the two are expecting Abigail to move in with them.

While struggling to overcome her natural suspicions of a note from beyond the grave (not to mention anything positive) Abigail tries to fit in with her strange, new American family: a distant father with a closed past, a too-perfect stepmother, and most puzzling of all, her long-lost sister. Becky sweeps Abigail into a shadowy underground movement involving clandestine street art, jailbreaks, and a bizarre double life. Soon, Abigail uncovers something unimaginable: a plot with vast implications, one that is aimed not only at controlling her sister, but the behavior of rebellious teens across the globe.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Helen Fitzgerald is a highly acclaimed and bestselling UK author, whose five thriller titles have sold over 125,000 copies in the UK and Europe. She worked as a parole officer and social worker for ten years before becoming a full-time writer. Dead Lovely is currently in film production. Her first YA, Amelia O'Donohue Is SO Not a Virgin, was published in 2010.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter One

The guy facing Abigail across the desk wasn’t her parent and he wasn’t her friend. “Sit down, Abi,” he said, with a voice that tried to be both. He wasn’t a social worker either,

more of an unqualified asshole. He did the Saturday night shifts. He slept when he was supposed to be keeping an eye on the residents. Abigail could get him sacked. Maybe she would if he called her Abi again.

“Abigail,” she corrected him, settling into the chair. She didn’t approve of nicknames. Nicknames were for people who were loved.

“Okay Abigail,” he said. “There, are you comfortable?”

“I’m okay,” Abigail said.

“I have very bad news, I’m afraid, Abi.”

“I told you, it’s Abigail,” she said through gritted teeth. She wasn’t impatient to hear the very bad news. Very bad news bored her, the certainty and regularity of it. It had

always been delivered in rooms like this; council issue rooms with vomit-resistant carpet, untidy desks marked with coffee cup rings, and stained ceilings. Always delivered by people like this; faces etched with fake concern that did not disguise the shopping lists being written in their heads.

The Dunoon social work office, for example, had the same Samaritan’s poster on the wall with the same suicide hotline number: “The children’s home you’re going to is in beautiful countryside,” the phony social worker had promised nine-year-old Abigail.

And at the Ardrossan Assessment Center, age fourteen, the same orange files were piled on top of the desk. “The residential school has an excellent reputation,” another

phony face had promised, “and it’s in the city. Won’t that be an adventure?”

Here she was, in another ugly room, waiting for another piece of ugly news. Unqualified asshole touched the orange file in front of him before saying what he had to say.

“ABIGAIL THOM” was written on top of the file in thick black pen. Underneath it was a long number: 50837. She was child number fifty-thousand-eight-hundred-and-thirty

seven, she supposed. This was her number. Her file. Her crappy paper life, written by people who jotted as they spoke to her, who refused to let her see what they had written, and then went home at night, stopping first for their shopping. She looked at the file as he touched it. One day, she would

like to read what was inside. It was her life after all. What

gave them the right to know while she didn’t?

“Your mother died last night,” he said.

Abigail heard the words, but all she could focus on was the coffee mug. “Glasgow City of Culture 1990” was etched on it.

“This is very difficult to take in, I know.” He paused before repeating the news. “Did you hear me? Your mother died last night.”

“Oh.” Abigail had whimpered accidentally. She didn’t like giving anything away. She swallowed, sat upright, and attempted to merge the whimper into something disarming

and matter-of-fact, thus: “Oh. Well thank you for telling me. Is that all?”

Unqualified asshole was disarmed. He had obviously been hoping for a big scene. He’d probably assumed she’d throw herself at him and cry into his thin bony shoulders. He was probably looking forward to going home and telling his roommate (no way did he have a girlfriend) that he had consoled a sixteen-year-old orphan, that he had held

her tight while she sobbed; that he, and only he, had helped today.

“Um, well actually, the nurse said your mother left something for you . . . at the Western Infirmary. Do you want me to take you there to pick it up?”

“No,” Abigail said. “I know where it is.”

The hospital was a five minute walk from New Life Hostel, the building she’d been forced to call home this last year. Six bedrooms, twelve residents. Abigail thought of

it as No Life Hostel. And while the residents were known as Homeless Young Adults or Care Leavers or The Looked After, Abigail preferred the truth to euphemisms: Unloved Nobodies.

She’d been an unloved nobody since nine, when Nieve died. Whoever Abigail’s dead mom was, she’d abandoned her when she was just three weeks old, leaving her in the care of a middle-aged hippy who lived on a commune, smoked pot, and played guitar. Lovely Nieve. Kind and caring and giving and all Abigail had known and all she had needed.

Her home with Nieve had been unconventional—they lived on an anti-nuclear camp in Western Scotland. US nuclear submarines were based in the area, and a community

had taken root to try and get them out. Nieve’s bright pink caravan had “Out Nukes!” painted in black on the side. There were bunk beds at one end of the caravan. Abigail

had the top bunk, with a wee window overlooking the Holy Loch. So it was unconventional, yes, but Nieve was wonderful and it was home. Nieve always made Scotch broth which simmered on the gas cooker. Abigail and the other children picked mushrooms in the autumn, sat by bonfires at night, told stories, walked to school together. Adults did the same except for the school part; they spent the school days plotting to make the world a better and a safer and a more just place. Funny: Abigail couldn’t remember anything beyond the first names of her childhood mates. Serena. Malcolm. Sunday, the baby. Who knows where they were now, what they’d become?

Not long after Abigail’s ninth birthday, Nieve was diagnosed with cancer. Within a month, she was dead.

After Nieve’s death, Abigail was visited by two men in jeans and driven away in a battered Ford Fiesta. They were social workers, they told her. They were taking her to a place called “care”. She had no idea what they meant, but as she sat in the Dunoon social work office an hour later among dirty coffee mugs, orange files and Samaritan’s posters, she knew it wasn’t a good thing. She didn’t even get to go to Nieve’s funeral, a Humanist service to be held near Tighnabruaich. That night the people in the commune were going to begin the celebration of Nieve’s life by painting her cardboard

coffin. Abigail regretted this more than anything: that she hadn’t been allowed to participate. She was going to paint two birds, flying free in clear blue sky. Nieve had always told her they were birds, the two of them. The social workers said she couldn’t go back to the commune ever again. They told her there were drugs on the commune;

that it was in her “best interest” to stay away from there.

So began seven years of being “looked after” in eight different establishments. Seven years of being examined and documented by early shift workers, late shift workers, night shift workers, field workers, adoption and fostering workers, and blah, blah, blah. Mumbo Jumbo: all of it and all of them. What was it that the Bible said? “Seven lean years?” Maybe the Bible wasn’t a total load of shit.

Her first social worker—one of the men in the Ford Fiesta—was Jason McVie. Long haired and laid back, like the men she had known on the anti-nuclear commune. Abigail felt comfortable with him. He gave her compassion and time. He valued her opinions. He stood up for her when care workers accused her of stealing money from the staff office (she hadn’t). Jason took her shopping when she had nothing to wear to the school dance. Abigail cared about Jason.

After two years on the job, Jason went off sick and then left to work in a bar in Majorca. He was sad when he said goodbye. He would never forget her, he said.

Three years later, Abigail bumped into him at Central Station in Glasgow. He had cut his hair short. He was pushing a buggy with a baby in it. His baby. Abigail raced up to him, excited. He looked as though he tried hard, but he could not remember her name. All he could offer was a vacant smile.

She never got close to anyone after that. And after several requests to visit her friends on the commune, she gave up asking, and never saw any of them again.

Abigail hurried from the office. She had to figure out what to do. Should she go now? The hospital was close, located in the same posh, trendy part of Glasgow. Both The Western Infirmary and No Life were beautiful Victorian buildings that disguised the misery within. Ironic that her mother had been so near when she’d died. Or was it ironic? Abigail had no idea where her mother had been living or what she’d been doing. All she knew was that sixteen years ago, her mother had arrived at Nieve’s protest camp one rainy Tuesday evening, and begged the kind hippie to take her newborn baby. “Keep her safe,” was all she’d said, according to Nieve. “Don’t tell her anything about me. And never try to contact me.”

“She was a good woman,” Nieve had told her more than once, “but she wasn’t able to look after you. Please don’t ask me anything else.”

At first Abigail didn’t need to know more than that because she was happy, and loved. But for some reason, on her ninth birthday, she decided she wanted to know what her mother looked like.

“Please! As a birthday present?”

“I’m sorry, darling, I can’t tell you anything. I promised.”

“Nieve, just a description. Please. I deserve that.”

Reluctantly, Nieve took the key that was always attached to the silver chain around her neck, unlocked the “chest of special things” she kept at the end of her bed and gave Abigail a photograph. In the small framed shot, colorful protesters marched in Glasgow’s George Square, holding placards that read NO NUKES!

“That’s me at the very front, and that’s her, there, the pretty one, third from the left in the second row. See? In orange and red? Same hair as you?”

Abigail scrunched her eyes to look at the tiny red and orange protester that was her mother, apparently.

“She has the same slim build as you, see!” Nieve said. “Thank God for small favors.”

Nine-year-old Abigail could only confirm that the woman in the photo was indeed slim and that her features were regular which meant there was a possibility that she

was pretty.

Abigail took the photo from Nieve and carried it with her everywhere from that day onwards. At the moment, it was in the inside pocket of her grey Nike backpack. Apart from Nieve’s silver chain with the key on it, which Abigail always wore around her neck, it was the only memento she had of anything remotely family. But the one thing that had always stuck with Abigail: Nieve was already dying then. And she probably knew it.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSoho Teen

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 1616954191

- ISBN 13 9781616954192

- BindingPaperback

- LanguageEnglish

- Number of pages248

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Deviant

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00026201809

Quantity: 1 available

Deviant

Seller: medimops, Berlin, Germany

Condition: very good. Gut/Very good: Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit wenigen Gebrauchsspuren an Einband, Schutzumschlag oder Seiten. / Describes a book or dust jacket that does show some signs of wear on either the binding, dust jacket or pages. Seller Inventory # M01616954191-V

Quantity: 1 available