Synopsis

“The greatest living realist painter” is how Robert Hughes described Lucian Freud in 1998. He is probably most famous as a portraitist, a portraitist above all of nudes. Stripped of their clothes, his sitters—mostly friends or family members—are revealed in all their vulnerability. Their gorgeously painted flesh is alive. As Freud himself has said of his nudes, “I used to leave the face to the last. I wanted the expression to be in the body. The head must be just another limb.”

Freud has always worked outside the conventions—academic as well as modernist—of contemporary art. However, his vision reflects the anguish of his time as powerfully as the work of his close friend, the late Francis Bacon, once did. Where Freud triumphs is in his ability to get inside his sitters: not to analyze them, as his grandfather did, but to bring them to sentient life in paint.

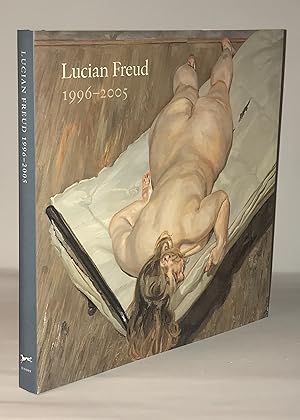

Although he works very slowly—most portraits take months to finish—Freud has spent the last ten years (since the publication of the 1996 monograph Lucian Freud) painting day after day, usually from 8 a.m. until midnight. The result has been a corpus of great new works, which reveal him to be the only heir today of Rembrandt, Courbet, and Cézanne.

The most daring of Freud’s recent portraits is a full-length painting of Andrew Parker-Bowles—a new, subtly satirical take on the grand manner that stretches back through van Dyck to Titian. Like Goya, Freud is without reverence. With his portrait of the Queen, you feel the canvas is a window through which Her Majesty is bursting, diadem and all. Freud has also indulged his passion for animals in some wonderfully perceptive studies of horses and his whippet, Pluto. And he has proved to be an acute observer of nature in obsessively meticulous but wonderfully fresh paintings and engravings of the buddleia bush in his garden. This book is a dazzling record of a powerful late period by our last great painter.

Lucian Freud was born in Berlin in 1922, the son of the architect Ernst Freud and the grandson of Sigmund Freud. His family moved to England in 1933. His work has been exhibited in major museums around the world with retrospectives at the Tate Gallery in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. He lives in London.

Reviews

Starred Review. Well into his ninth decade, the painter Lucian Freud (grandson of Sigmund) not only shows no signs of slowing down, he hasn't even adopted a signature "late style." Although most of the paintings and drawings in this marvelous collection are characteristically concerned with the human body, the painter's dogs are frequently (and vividly) present; there are a number of landscapes (including an evocative Constable tribute); and his portraits include a number that are focused very tightly on the face. These portraits—very small scale, and with an exaggeration of detail that miraculously avoids caricature—culminate in Freud's controversial portrait of Queen Elizabeth II. A charming photograph records her sitting for the painting—the artist looks away from his tiny canvas while the monarch regards him with a look of wry amusement. The final portrait captures not only the queen's regal hauteur but also the defiance of a tough old granny whose life has been far from easy. This broad sympathy for the ways in which experience marks our faces and bodies has deepened in Freud—if he is "mellowing" at all it is toward an interest in character as strong as his interest in the flesh that contains it. The reproductions are of unusually high quality—Freud's highly worked and pebbled surfaces seem to stand out from the page. (Nov. 17)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Some critics call Freud the only significant realist painter around these days, which surely must give untutored viewers of his work pause. Oh, yes, Freud's garden paintings are all very nice, what with their variety of painterly manners, from sharp delineation of leaves to impressionistic conjuring of compound flowers; their ambiguous perspective, in which perceived depth oscillates as it does to the eye in bright, outdoor light; and their all-over compositional feel, akin to that of Jackson Pollock canvases. And the horse and dog studies, with their sense of true relaxation, are unsentimentally appealing. But the portraits and more-often-than-not-nude figure paintings--the bulk of his most celebrated work? One could be forgiven for thinking them off-puttingly blotchy and lumpy, and, in the nudes, too naked. Thus, it is very fortunate that these pictures are so incisively introduced here by Sebastian Smee, calling attention to their allusions, the implications of their brushwork and impasto, and Freud's hopes for his achievement in them. One can look again--and start to really see. Ray Olson

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.