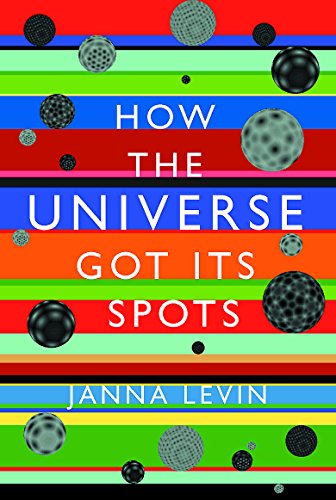

Conventional wisdom says the universe is infinite. But could it be finite, merely giving the illusion of infinity? Modern science is beginning to drag this abstract issue into the realm of the real, the tangible and the observable. HOW THE UNIVERSE GOT ITS SPOTS looks at how science is coming up sharp against the mind-boggling idea that the universe may be finite. Through a decade of observation and thought-experiment, we have started to chart out the universe in which we live, just as we have mapped the oceans and continents of our planet. Through a kind of cosmic archaeology and without leaving Earth, we can look at the pattern of hot spots left over from the big bang and begin to trace the 'shape of space'. Beautifully written in a colloquial style by a world authority, Janna Levin explores our aspirations to observe our universe and contemplate our deep connection with it.

How the Universe Got its Spots is the diary of a couple of years in the life of Janna Levin, a young theoretical physicist specialising in cosmology. Combining a discussion of her research with more personal reflections on how her work and personal life interact, it's a warm and revealing record of the working life of a scientist.

Levin's current specialism is topology, the global shape and connectedness of space. With the aid of numerous diagrams she manages to explain the basic ideas in lay terms, which is no mean feat for a theory that strives to move beyond Einstein. General relativity tells us how space curves locally, but it can't determine the overall shape of the universe, nor whether it's infinite or bounded. If it's finite, light travelling in a straight line will eventually return to its starting point, like a ship sailing around the Earth. In a tiny universe we would see multiple copies of ourselves as light circled around and around. The real universe is at least billions of light years across, and Levin is modelling the patterns of spots that would appear in the microwave background radiation if space had various different topologies.

One day, orbiting telescopes may give us the data we need to determine the actual shape of the universe. We may not have the answers yet, but what this book does have is a real insight into the motivations of a theoretical physicist as she plays with notions so far beyond everyday life that they boggle the mind. It's reassuring to know that Levin is boggling too. --Elizabeth Sourbut

![]()