Bradley Steffens

I was born in Waterloo, Iowa—Ioway as my maternal grandfather pronounced it. My family moved to Tucson, Arizona, when I was two. I don't remember Iowa or the trip to Arizona, but I do remember the Mayflower moving van backing into our driveway on Eli Drive and crushing one of the concrete curbs—an early lesson in the transience of this world.

I also remember playing with the sand between the stones in the driveway, looking up, and seeing a monster headed straight at me. I ran to my father, imploring him to get his shotgun. "Well, let's take a look at this monster," he said. When he saw it, he said, "I don't think I need my shotgun. I think I can use the rake." He lifted the thick, brown worm—at least a foot long—off the driveway and tossed it over the back wall into the alley. I was amazed at his courage and ingenuity.

My father was a machinist, a turret lathe operator. When he was laid off from Hughes Aircraft, he traveled to Los Angeles and got a job making parts for the Apollo space program. We sold the house in Tucson and joined him in Canoga Park. I was ten.

I attended Sunnybrae Elementary School. One of the teachers there, Betsy Crawford, encouraged my writing. I had a rubber-stamp printing set and my father had taught me to touch type on an old Royal manual typewriter. I used to make sports broadsides for his amusement. He told Betsy Crawford about my hobby, and she suggested that I try writing newspaper accounts of historical events. I did, and Betsy reproduced my work on a mimeograph machine and gave copies to the class—my first publication but also a source of keen embarrassment as the other students called me "teacher's pet."

I attended Sutter Junior High and was awestruck by the massive, delicately colored mural in the library. It was painted by the Danish artist Kay Nielsen, who had traveled to Southern California to work at Disney Studios. Nielsen worked on a version of "The Little Mermaid" that was never released, but he did receive a posthumous credit for the 1992 version.

I served as student body president at Sutter, representing the school when it received an award from the Freedom Foundation in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. That was my first trip to the East Coast, and I was awed, perhaps most of all by the trees. Growing up in Arizona and California, I finally understood why the European settlers had to clear the trees.

During the L.A. teacher's strike of 1970, I collected some interviews with striking teachers that the principal had ordered removed from the school newspaper and published them in an underground newspaper. I also wrote a critique of the administration, which did not seem to be living up to the ideals of the award the school had received. I was suspended for the duration of the strike—an experience that helped inform the five or six books I have written about free speech and censorship.

As a former student body president and holder of many offices, I was in line to receive several graduation awards, but I got none. I was bewildered. My counselor, Mr. Wright, saw I was crestfallen and took me into his office. "You were nominated for every award," he told me, "but you were blackballed because of your underground paper." Mr. Wright looked me in the eye. "I want you to know that I believe you will go on to accomplish more than any of the students who received awards." It was the kindest, most helpful thing anyone had ever said to me. I walked out of his office with my head held high.

I moved on to Canoga Park High School, where I excelled at English and golf, making varsity all three years I was there. I wrote my first published poem as an assignment in Jim Malone's creative writing class at Canoga Park High School in 1972. I won the competition to give a speech at graduation with a poetic meditation aimed at capturing the zeitgeist of the early 1970s.

I attended Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota, for a year. It was a fantastic experience, but one I could not afford. I took John Bernstein's Modern Poetry, Peter Murray's Shakespeare, Robert Warde's Nineteenth Century Fiction, Alvin Greenberg's Modern Novel, and an independent study course with Roger Blakely on Emily Dickinson--a course that influenced my 1996 biography of the great poet.

I published a few poems over the next few months. In 1975, I self-published a 28-page chapbook of poems. I supported myself as a street poet for a couple of years, including a year I lived in Ajijic, Mexico. Many more published poems followed, some winning various literary prizes, including including the Emerging Voices Award presented by The Loft Literary Center, the Lake Superior Writing Competition sponsored by the Duluth Public Library, and the annual poetry contest sponsored by the Saint Paul chapter of the American Association of University Women.

Inspired by Browning's poetic monologues and Yeats' "Plays for Dancers," I began writing dramatic poetry. In 1981, the Olympia Arts Ensemble in Minneapolis produced an evening of my plays-in-verse. I was twenty-five and failed to fully appreciate what an amazing thing that production actually was. Noel Bredahl of the St. Paul Post-Dispatch hailed the play as "an awesome creation on the part of the playwright." David Hawley, also of the St. Paul Post Dispatch, wrote, “Steffens is a powerful, talented artist."

I published my first nonfiction book in 1989. I have followed it with more than forty more, including "Ibn al-Haytham: First Scientist,"the first full biography published in English about the eleventh-century Muslim scholar who pioneered experimental science. At the suggestion of Ruth Marvin Webster, a reporter with the North County Times in Escondido, California, who interviewed me about "First Scientist," I tried my hand at turning the biography into a historical novel. The result of this five-year effort, "The Prisoner of Al-Hakim," was published by Blue Dome Press in 2017. I am currently working on a sequel as well as writing nonfiction books for Referencepoint Press.

Popular items by Bradley Steffens

View all offers-

-

Understanding Of Mice and Men (Understandig Great Literature)

Steffens, Bradley

Item prices starting from

View 7 offersUS$ 7.84

-

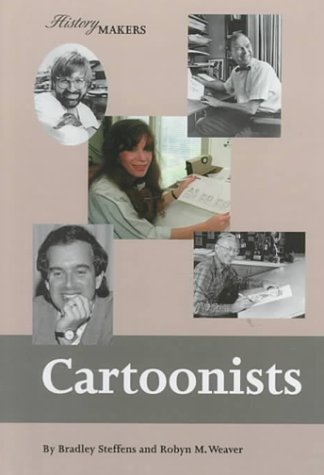

Cartoonists (History Makers)

Steffens, Bradley; Conley-Weaver, Robyn

Item prices starting from

View 3 offersUS$ 8.27

Also find

Used -

Free Speech: Identifying Propaganda Techniques (Opposing Viewpoints Juniors)

Steffens, Bradley; Buggey, Joanne

Item prices starting from

View 7 offersUS$ 6.98

-

The Encyclopedia of Discovery and Invention - Phonograph: Sound on Disk

Steffens, Bradley

Item prices starting from

View 1 offerUS$ 9.98

Also find

Used -

The Fall of the Roman Empire: Opposing Viewpoints (GREAT MYSTERIES)

Steffens, Bradley

Item prices starting from

View 1 offerUS$ 10.36

Also find

Used -

The Loch Ness Monster (Exploring the Unknown)

Steffens, Bradley

Item prices starting from

View 1 offerUS$ 9.99

Also find

Used -

Teen Suicide on the Rise (Mental Health Crisis)

Steffens, Bradley

Item prices starting from

View 2 offersUS$ 7.98

Also find

Used

You've viewed 8 of 69 titles