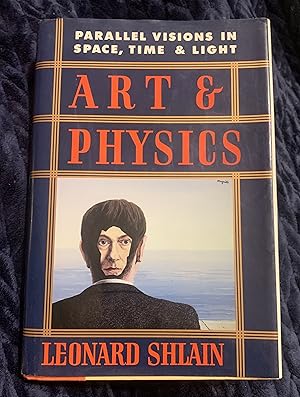

Synopsis:

Studies the way science has influenced the artistic imagination throughout history, such as the parallel between Einstein's theory of relativity and the work of Cezanne, Monet, and the other Impressionists

Reviews:

Leonardo da Vinci's complex sequential drawings, of pigeon wings fluttering in flight and of patterns made by fast-flowing water, anticipated time-lapse photography by 300 years. Surrealist painters' space-time distortions seemingly foreshadowed Einstein's theory of relativity. Franz Kline and Kazimir Malevich attempted to make abstract paintings devoid of image, color and light years before physicists fully accepted the notion that black holes could exist. Using these and other examples, Shlain, a Northern California surgeon, advances his thesis that art is precognitive: artists conjure up revolutionary images and metaphors comprising preverbal expressions of the novel concepts later formulated by physicists. He roots his theory in brain research and in a Jungian archetypal unconscious said to be stored in DNA strands. His provocative discussion is rigorous enough to appeal to the skeptical scientist yet wholly accessible and engaging to the art lover or general reader. Many potential connections between art and science are brought into full focus, aided by scores of art reproductions, photographs and diagrams.

Copyright 1991 Reed Business Information, Inc.

A California surgeon explores the striking parallels in the evolution of Western art and science in this enlightening exploration of where ideas come from and how they enter the consciousness of a culture. Though art and science are traditionally considered antithetical disciplines--with art dependent on intuition for its development and science on logic and sequential thinking--both nevertheless rely on an initial burst of inspiration regarding the nature of reality, and in Western culture the two have followed separate but remarkably similar paths. Shlain offers detailed anecdotes from the history of Western culture--from the ancient Greeks' penchant for single-melody choruses and blank rectangles, through the fragmented art and science of the Medieval period, to modern art's redefinition of reality and the relativity revolution in science--to illustrate how major movements in art have generally preceded scientific breakthroughs based on equivalent ideas, despite the artists and scientists involved having remained largely ignorant of one another's work. Shlain's suggestion that scientists have not so much been inspired by artists but have received initial inspiration from the same source--bringing to mind the possibility of a universal mind from which such ideas spring--is an intriguing one that offers a new window through which to view the dissemination of knowledge and ideas. A fascinating and provocative discussion--slow in coalescing but worth the wait. (Seventy-two b&w photographs and 15 diagrams.) -- Copyright ©1991, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved.

Shlain, a California surgeon, has bravely ventured into two disparate areas beyond the reach of his certified expertise in the medical sciences. He presents herein a number of periods in the history of art and the history of physics, comparing and contrasting the prevailing theories in each of these fields in different eras. Although they are commonly seen as being very different--or even opposite--the author argues that there are striking parallels in the histories of the two fields. He further states that "revolutionary art anticipates visionary physics," thus asserting an actual connection between the two. The book is provocative and, of course, likely to be controversial; physicists are especially likely to be skeptical of his thesis. Recommended for academic and large public libraries.

- Jack W. Weigel, Univ. of Michigan Lib., Ann Arbor

Copyright 1991 Reed Business Information, Inc.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

![]()