Items related to Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed...

Founded by Feliks Dzierzynski, the Cheka–the Extraordinary Commission–came to life in the first years of the Russian Revolution. Spreading fear in a time of chaos, the Cheka proved a perfect instrument for Stalin’s ruthless consolidation of power. But brutal as it was, the Cheka under Dzierzynski was amateurish compared to the well-oiled killing machines that succeeded it. Genrikh Iagoda’s OGPU specialized in political assassination, propaganda, and the manipulation of foreign intellectuals. Later, the NKVD recruited a new generation of torturers. Starting in 1938, terror mastermind Lavrenti Beria brought violent repression to a new height of ingenuity and sadism.

As Rayfield shows, Stalin and his henchmen worked relentlessly to coerce and suborn leading Soviet intellectuals, artists, writers, lawyers, and scientists. Maxim Gorky, Aleksandr Fadeev, Alexei Tolstoi, Isaak Babel, and Osip Mandelstam were all caught in Stalin’s web–courted, toyed with, betrayed, and then ruthlessly destroyed. In bringing to light the careers, personalities, relationships, and “accomplishments” of Stalin’s key henchmen and their most prominent victims, Rayfield creates a chilling drama of the intersection of political fanaticism, personal vulnerability, and blind lust for power spanning half a century.

Though Beria lost his power–and his life–after Stalin’s death in 1953, the fundamental methods of the hangmen maintained their grip into the second half of the twentieth century. Indeed, Rayfield argues, the tradition of terror, far from disappearing, has emerged with renewed vitality under Vladimir Putin. Written with grace, passion, and a dazzling command of the intricacies of Soviet politics and society, Stalin and the Hangmen is a devastating indictment of the individuals and ideology that kept Stalin in power.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Instead of saying something like “X was raised by crocodiles in a septic tank in Kuala Lumpur,” they tell you about a mother, a father . . .

Martin Amis, Koba the Dread

In the Russian empire, especially Georgia, 1878 was not a bad year to bring a child into the world. True, Georgians of all classes seethed with resentment. Their Russian overlords, into whose hands the last Georgian kings had surrendered their shattered realm at the beginning of the nineteenth century, ruled the country through a bureaucracy that was often callous, corrupt, and ignorant, while those Georgian children who went to school were instructed in Russian. The Russian viceroy in Tbilisi, however humane and liberal, was determined to keep things as they were: Armenians ran commerce, foreign capitalists controlled industry, while Georgian aristocrats and peasants, upstaged in their own capital city, led a more or less tolerable life in the fertile countryside.

Georgians had some reasons to be grateful for Russian rule. For nearly a century Georgia had been free of the invasions and raids by its neighbors that had devastated and periodically nearly annihilated the nation since the thirteenth century. Russians might impose punitive taxes, Siberian exile, and cultural humiliation, but, unlike the Turks, they did not decapitate the entire male population of villages and, unlike the Persians, they did not drive away the survivors of massacres to be castrated, enslaved, and forcibly converted to Islam. Under Russian rule towns had been rebuilt and railways linked the capital to the Black Sea, and thus the outside world. The capital city, Tbilisi, had newspapers and an opera house (even if it had no university). A new generation of Georgians, forced to become fluent in Russian, realized the dreams of their ancestors: they were now treated as Europeans, they could study in European universities and become doctors, lawyers, diplomats—and revolutionaries. Many Georgians dreamed of regaining independent statehood; so far, few believed that they should work toward this by violence. Most Georgians in the 1870s grudgingly accepted Russian domination as the price of exchanging their Asiatic history for a European culture.

For the inhabitants of the empire’s metropolis, St. Petersburg, 1878 was a year that threatened to totter into anarchy. The terrorists who would kill Tsar Alexander II in 1881 were already tasting blood: the honeymoon between the Russian government and its intellectuals and new professional classes was over. The seeds of revolution found fertile ground not in the impoverished peasantry nor in the slums that housed the cities’ factory workers, but among the frustrated educated children of the gentry and the clergy who were not content to demand just human rights and a constitution. They went further and were plotting the violent overthrow of the Russian state. Such extremism might be fanatical but was not unrealistic. A rigid state is easier to destroy than to reform, and the Russian state was so constructed that a well-placed batch of dynamite or a well-aimed revolver, by eliminating a handful of grand dukes and ministers, could bring it down. The weakness of the Russian empire lay in its impoverished social fabric: the state was held together by a vertical hierarchy, from Tsar to gendarme. In Britain or France society was held together by the warp and weft of institutions—judiciary, legislature, Church, local government. In Russia, where these institutions were only vestigial or embryonic, the fabric was single-ply.

The killers of Tsar Alexander II, the generation of Russian revolutionaries that preceded Lenin, saw this weakness but they had no popular support and no prospect of achieving mass rebellion. Russia in the 1880s and 1890s was generally perceived as stagnant, retrograde, even heartless and cynical—but stable. Episodes of famine, epidemics, and anti-Jewish progroms rightly gave Russia a bad international name in the 1880s. The 1860s and 1870s had been a period of reform, hope, and, above all, creativity: Fiodor Dostoevsky, Ivan Turgenev, Leo Tolstoi, and Nikolai Leskov were writing their greatest novels. But the zest was gone: only the music of Piotr Tchaikovsky and the chemistry of Dmitri Mendeleev testified to Russian civilization. Nevertheless, there was tranquillity in stagnation. This was the Russian empire’s longest recorded period of peace. Between Russia’s victory over Turkey in 1877 and its defeat by Japan in 1905, half a human lifetime would elapse.

Around the time Ioseb Jughashvili was born on December 6, 1878, in the flourishing town of Gori, forty miles west of Tbilisi, the atmosphere among the town’s artisans, merchants, and intellectuals was quietly buoyant. A boy whose parents had a modest income could secure an education that would make a gentleman of him anywhere in the Russian empire. Few observers had cause to agree with the prophecies of Dostoevsky and the philosopher Vladimir Soloviov: that within forty years a Russian tyranny so violent and bloody would be unleashed that Genghis Khan’s or Nadir Shah’s invasions would pale into insignificance by comparison. Even less did anyone sense that Ioseb Jughashvili, as Joseph Stalin, would be instrumental in establishing this tyranny over the Russian empire and would then take sole control of it.

yyyThe family that begot Ioseb (Soso) Jughashvili had no more reason than other Georgians to fear the future. The cobbler Besarion Jughashvili was in 1878 twenty-eight years old, a skilled and successful artisan working for himself; he had been married six years to Katerine (Keke), who was now twenty-two. She was a peasant girl with strong aspirations, well brought up, and had even been taught to read and write by her grandfather. Their first two sons had died in infancy; this third son, by Georgian (and Russian) tradition, was a gift from God, to be offered back to God. Katerine Meladze’s father had died before she was born, and she was brought up by her uncle, Petre Khomuridze. In the 1850s the Khomuridzes had been serfs from the village of Mejrokhe near Gori but in 1861 Tsar Alexander II made them, like all serfs, freemen. Petre Khomuridze, once freed, proved an enterprising patriarch: he raised his own child and the children of his widowed sister. Katerine’s brothers Sandro and Gio became a potter and a tile-maker respectively; when Katerine became a cobbler’s wife, all the Meladze siblings had succeeded in rising from peasant to artisan status.

The family of Stalin’s father Besarion seemed to be on the same upward course. Stalin’s paternal great-grandfather, Zaza Jughashvili, had also lived near Gori, in a largely Osetian village. Zaza was also a serf. He took part in an anti-Russian rebellion in the 1800s, escaped retribution and was resettled, thanks to a charitable feudal prince, in a hovel in the windswept and semi-deserted village of Didi Lilo, ten miles north of Tbilisi. Here Zaza’s son Vano moved up the social ladder: he owned a vineyard. Zaza’s two grandchildren Giorgi and Besarion seemed destined to climb further. After Vano’s death, Giorgi became an innkeeper but their rise to prosperity was brutally interrupted: Stalin’s uncle Giorgi was killed by robbers, and his younger brother Besarion, destitute, left for Tbilisi to be a cobbler. By 1870 the Jughashvilis had resumed their climb: working for an Armenian bootmaker, Besarion acquired not only his craft, but learned to speak some Russian, Armenian, and Azeri Turkish, as well as Georgian. Unlike most Georgian artisans at that time, Besarion was literate.

One in three great dictators, artists, or writers witness before adolescence the death, bankruptcy, or disabling of their fathers. Stalin, like Napoleon, Dickens, Ibsen, and Chekhov, was the son of a man who climbed halfway up the social ladder and then fell off. Why did Besarion Jughashvili fail, when everything seemed to favor a man of his origins and skills? Contemporaries recall little of Besarion. One remembers that the Jughashvilis never had to pawn or sell anything. Another remembers: “When Soso’s father Besarion came home, we avoided playing in the room. Besarion was a very odd person. He was of middling height, swarthy, with big black mustaches and long eyebrows, his expression was severe and he walked about looking gloomy.” Whatever the reasons, in 1884, when Stalin was six, Besarion’s affairs went sharply downhill. The family moved house—nine times in ten years. The cobbler’s workshop lost customers; Beso took to drink.

Early in 1890 the marriage of Stalin’s parents broke up. This was the last year the young Stalin had any contact with his father: the twelve-year-old boy was run over by a carriage and his father and mother took him to Tbilisi for an operation. Besarion stayed in the capital, finding work at a shoe factory. When the boy recovered, Besarion gave him an ultimatum: either become an apprentice cobbler in Tbilisi or return to Gori, follow his mother’s ambitions, train to be a priest, and be disowned by his father. Soso went back to school in Gori in autumn 1890. Besarion, after visits to Gori to beg Katerine to take him back, vanished. (Stalin later stated in official depositions that his father had abandoned the family.) Besarion Jughashvili became an alcoholic tramp. On August 12, 1909, taken to the hospital from a Tbilisi rooming house, he died of liver cirrhosis. He was buried in an unmarked grave, mourned only by one fellow cobbler.

Some Georgians found it hard to believe that Stalin could have such lowly origins: they speculated that Stalin was illegitimate, which would explain Besarion deserting his “unfaithful” wife and her offspring. Legend puts forward two putative fathers for Stalin: Nikolai Przhevalsky, explorer of central Asia, and a Pr...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0375506322

- ISBN 13 9780375506321

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages576

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

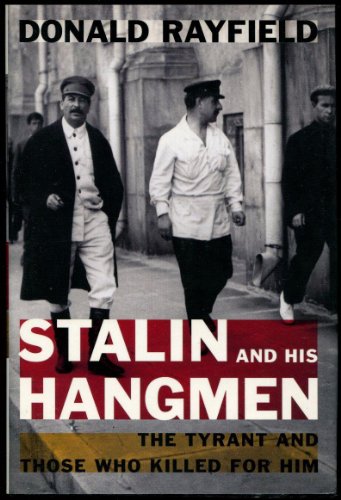

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. Hardcover and dust jacket. Good binding and cover. Clean, unmarked pages. Seller Inventory # 2404270014

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: As New. Seller Inventory # ABE-1698441668851

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # N9-ZLQV-L0QO

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_0375506322

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0375506322

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk0375506322xvz189zvxnew

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0375506322-new

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0375506322

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0375506322

Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0375506322