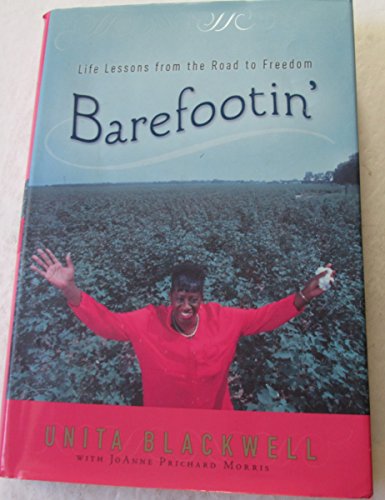

Items related to Barefootin': Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom

You have to have faith to go barefooted—you don’t know what you might step on, what pain might come—but you keep on walking. And it makes you tough. Sometimes you skip and jump and run. Sometimes you get a thorn in your toe or trip over a limb, but there’s no turning back.

Barefootin’ means getting mud between your toes and dancing on the water! Your spirit is in your feet, and your spirit can run free.

In 1933, Unita Blackwell was born in Lula, Mississippi, a tiny town in the Delta where living was as hard as it gets, the stuff of the blues music that originated there. Like the other black people in Lula, Unita grew up in a sharecropping family, riding on her mother’s cotton sack before she was old enough to pick cotton herself. Having left school at age twelve in order to make a living, Unita was trapped in menial jobs, and a bright future seemed beyond her reach.

But Unita was forever changed in the summer of 1964 when civil rights workers came to her town of Mayersville, Mississippi. Electrified by the movement, Unita transformed her life from one of despair to one of hope, and in Barefootin’ she details her inspirational rise from poverty to power, from silence to outspokenness, from oppression to freedom.

From her rebirth as a freedom fighter and social activist to her tenure as mayor of her home town, to her work as an international peacemaker and presidential advisor, here are all the unlikely turns of Unita’s remarkable life. The lessons she shares affirm and motivate us all, whether it’s to remember that ordinary people can do extraordinary things, that world-changing movements are the result of many small steps, or that freedom means taking responsibility for our own lives and helping to make the world a better place for all.

Infused with the language and rhythms of the Delta, Barefootin’ is at once the stirring memoir of an exceptional woman and a guide to living a full and meaningful life from someone who knows how.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

JoAnne Prichard Morris is an editor, writer, and publisher. She worked closely with her late husband, Willie Morris, on many of his books, including My Dog Skip. She lives in Jackson, Mississippi.

THE NEWS WHIPPED THROUGH Mayersville like a brushfire: "A bunch of niggers are over at the courthouse." And soon a gang of folks had gathered to see what was going on.

There were eight of us standing in a cluster by the side door of the Issaquena County Courthouse--me and my husband, Jeremiah, Mrs. Ripley, the Siases, and three schoolteachers. I probably stood out in the group since I'm close to six feet tall and near about as black as a person can be. People hadn't ever seen anything like this in our little Mississippi Delta town--black folks didn't hang around the courthouse. Hardly any blacks ever had reason to go to the courthouse at all. And nobody was expecting to see us that morning. Most of the time when black people congregated on the street, they were waiting for a ride to the cotton field or on their way to church. Anybody could tell we weren't going to the field that day because we didn't have on our loose ragged work clothes; we weren't all dressed up for church, either. We were dressed plain but neat. We had come to register to vote.

At that time--June of 1964--only twenty thousand black people were registered to vote in the state of Mississippi. And not a single one of those lived in Issaquena County, way down in the toe of the Mississippi Delta, even though two-thirds of the folks in the county were black. Jeremiah and our seven-year-old son, Jerry, and I lived in a falling-down three-room house that had belonged to Jeremiah's grandmother. I was thirty-one years old, stuck in poverty, and trapped by the color of my skin on a rough road to nowhere, doing what Mississippi black people had been doing for generations--working in the cotton fields. I would've been out chopping cotton that day if two young fellows from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)--"Snick" they called it--hadn't come to town the week before, asking for volunteers to register to vote.

We hadn't been at the courthouse very long when Sheriff Darnell came strolling by. He stopped and rolled his eyes at us, like we were children acting up.

"What are y'all doing here?" The sheriff was playing dumb; he knew full well that the civil rights folks had been in town meeting with us.

"We come to register to vote," I said.

"Vote? What you think you gonna get out of that?"

"It's our right as Americans. The Constitution says so." I had already learned a lot from the civil rights guys.

"Them outside agitators in town have got y'all all riled up," he said. "They'll go on back to wherever they come from in a little while, but you niggers gotta live here all the time, you know. If I was you, I'd get myself on back home." He wasn't real gruff. In those days he didn't even have to raise his voice to get black folks to do what he told them to.

But I said, "No, sir, Sheriff Darnell, we ain't leaving. I believe we'll just stay here until we get in to see Mrs. Vandevender."

Mrs. Mary Vandevender was the circuit clerk for the county, and she was the one who'd give the voter registration test to us. I knew about the test. I'd have to fill out a long application, read a section of the state constitution, and "interpret" it in writing. Whether you passed or not was left entirely up to the person giving the test. That was the law in Mississippi, and that's the way black people had been kept from voting for years, if they ever got that far along in the process. The last time any blacks had tried to register in Issaquena County was about 1950--two fellows who had come home from the Army--and they were turned away at the courthouse door.

"Well, can't but one of you go in there at a time," Sheriff Darnell said. "And the rest of y'all, get over there across the street. It's against the law to stand up this close to the courthouse."

We agreed that since Minnie Ripley was the oldest, she ought to be the first to go in. "Mother Rip" was in her seventies and had lived in Mayersville all her life. Everybody, black and white, knew her and respected her. She was a devoted church worker. She wasn't a very big lady, but she had a big presence about her and always a spring in her step, and she pranced right on into the courthouse.

The rest of us crossed the street to stand under a couple of big oak trees, and Sheriff Darnell ambled off. It was still fairly early in the morning, but the summer sun was already bearing down, and even with my straw sun hat on, I was glad to get in the shade. The grass was worn down under the tree, and we hadn't had a sprinkle of rain in over a month, so the dust was thick and got all up in between my toes in those old slides I was wearing. I had no idea what I was in for, and I must have been anxious and tense, but today, at the age of seventy-two, I remember only how clear my mind was and how determined and strong I felt.

As soon as Mrs. Ripley went inside the courthouse and the sheriff left, Preacher McGee came hustling over to us. A wiry, light-brown-skinned fellow, he was what we called a "jackleg" preacher, one who doesn't have a regular church of his own.

"Y'all need to get on away from here," Preacher McGee said. "Don't stir up nothing." He was nervous and talking fast.

We knew that the sheriff--or some other white man--had enlisted him to convince us to leave. You always had black folks like Preacher McGee who did what the white men told them to. Some of them were scared not to. Others just wanted to pick up a dollar or two. I believe Preacher fit both of those categories.

Soon a bunch of white fellows came driving up in their pickup trucks and started circling the courthouse. Guns were hanging on gun racks in the back window for all of us to see. This was the first time I ever saw guns displayed that way. Before the 1960s, white men did not usually ride around town with a rack of guns in their trucks. You might have seen a gun every once in a while when the person was going out hunting deer or rabbits or something. Those men weren't hunting rabbits that day.

The men parked their pickups on the street around the courthouse, hemming us in. There were half a dozen trucks, as I recall. They hollered at us from inside their trucks: "Niggers, niggers. Go home, niggers." The sheriff came walking by again. By this time he had picked up his pace and was shouting at us: "Y'all go on home. Get on away from here." Preacher McGee kept walking around, twitching and pleading with us, "Come on, y'all, come on. They mad. Come on, come on. Y'all better come on now."

But we did not leave.

The men climbed out of their trucks and walked over to where we were standing. They brought their long hunting guns with them. I'd seen these men around town and knew who they were--farmers, most of them. They stopped right in front of us and stood there glaring. Nobody said a word. Their faces were bright red. I had never before seen that kind of rush of blood in a person's face. In those days a black person wasn't supposed to make eye contact with whites. But I looked right into the eyes of one of those white fellows. And he looked straight at me, and if eyes could have shot me down, they would have done it. Hate mooned out just like a picture.

I didn't know what was going to happen next or what I would do. I didn't have a gun or any other weapon to protect myself. None of us did. SNCC believed in nonviolence, and we were following SNCC. I was frozen with fear.

Pictures were flashing through my mind: the three civil rights workers who had gone missing in Neshoba County just the week before; Medgar Evers, murdered the previous summer, shot in the back while his wife and little children watched; Emmett Till at the bottom of the Tallahatchie River with a cotton gin fan tied around his neck. I had learned about these violent acts soon after they happened, and others like them, and I knew they were true. But they had never seemed real to me until that day. I had never believed or accepted or understood that something like that could actually happen to me. From birth I'd been taught not to hate white people, or anyone, to work hard and treat people right, and to have faith that goodness would win out over evil and hatred. Even the undeniable reality of my own grandfather's horrendous death did not take hold of me until that day, although I had heard the story dozens of times and knew it well.

My granddaddy, Daddy's father, was working on a sugar plantation down in Louisiana, where he'd grown up and where his own mother had been a slave. One day the white man that owned the plantation accused my grandfather of something. I don't know what it was, whether it was trivial or serious, but, whatever it was, my grandfather was not at fault.

"I did not do that, boss."

"Nigger, are you 'sputing me?"

"No, sir, I ain't 'sputing you. I'm just telling you the truth: I didn't do it."

"No nigger of mine will 'spute me."

And the white man shot him. Killed him dead, right there in the cane field.

The horror of that story and everything came together for me the day those white men with guns surrounded me at the courthouse. I could taste and smell reality. These white men--people I saw around town, who sometimes even smiled and spoke to me--were so consumed with hatred for me that one of them might actually kill me just to keep me from registering to vote. If our first small step toward freedom--registering to vote--threatened white folks that much, I knew then that the right...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherCrown

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0609610600

- ISBN 13 9780609610602

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Barefootin': Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0609610600

Barefootin': Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0609610600

Barefootin': Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0609610600

Barefootin': Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0609610600

Barefootin': Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0609610600

Barefootin': Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0609610600

BAREFOOTIN': LIFE LESSONS FROM T

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.05. Seller Inventory # Q-0609610600