Synopsis

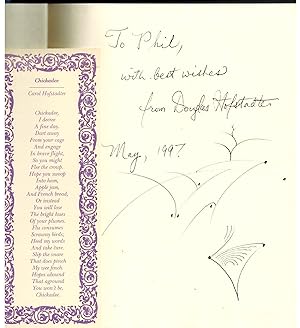

Lost in an art—the art of translation. Thus, in an elegant anagram (translation = lost in an art), Pulitzer Prize-winning author and pioneering cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter hints at what led him to pen a deep personal homage to the witty sixteenth-century French poet Clément Marot.” Le ton beau de Marot ” literally means ”The sweet tone of Marot”, but to a French ear it suggests ”Le tombeau de Marot”—that is, ”The tomb of Marot”. That double entendre foreshadows the linguistic exuberance of this book, which was sparked a decade ago when Hofstadter, under the spell of an exquisite French miniature by Marot, got hooked on the challenge of recreating both its sweet message and its tight rhymes in English—jumping through two tough hoops at once.In the next few years, he not only did many of his own translations of Marot's poem, but also enlisted friends, students, colleagues, family, noted poets, and translators—even three state-of-the-art translation programs!—to try their hand at this subtle challenge.The rich harvest is represented here by 88 wildly diverse variations on Marot's little theme. Yet this barely scratches the surface of Le Ton beau de Marot , for small groups of these poems alternate with chapters that run all over the map of language and thought.Not merely a set of translations of one poem, Le Ton beau de Marot is an autobiographical essay, a love letter to the French language, a series of musings on life, loss, and death, a sweet bouquet of stirring poetry—but most of all, it celebrates the limitless creativity fired by a passion for the music of words.Dozens of literary themes and creations are woven into the picture, including Pushkin's Eugene Onegin , Dante's Inferno, Salinger's Catcher in the Rye , Villon's Ballades, Nabokov's essays, Georges Perec's La Disparition, Vikram Seth's Golden Gate, Horace's odes, and more.Rife with stunning form-content interplay, crammed with creative linguistic experiments yet always crystal-clear, this book is meant not only for lovers of literature, but also for people who wish to be brought into contact with current ideas about how creativity works, and who wish to see how today's computational models of language and thought stack up next to the human mind. Le Ton beau de Marot is a sparkling, personal, and poetic exploration aimed at both the literary and the scientific world, and is sure to provoke great excitement and heated controversy among poets and translators, critics and writers, and those involved in the study of creativity and its elusive wellsprings.

Reviews

Clement Marot (1496-1544) may have been a great French poet, but "A une Da-moyselle malade" is not his best effort. Essentially it's a get-well greeting: sorry that you're sick, but try to eat something and get some fresh air. The ditty serves as a springboard for Hofstadter's thoughts about language, translation, culture and human genius as the author, his friends, translators, scholars and even computer programs contribute to numbing permutations of this one weak lyric. Hofstadter, a professor of artificial intelligence at Indiana University, had bestsellers with the 1980 Pulitzer Prize-winning Godel, Escher, Bach and a collection of essays reprinted from Scientific American, called Metamagical Themas. Here he is on shakier ground. Hofstadter is not a poet but doesn't hesitate to lay out his opinions: for example, all rhyming translations of "Eugene Onegin" are "excellent" and "fine," but he trashes Vladimir Nabokov's monumental and helpful literal version; he also calls Lolita "pedophilic pornography." And while there are moments of wit, intelligence and uncommon curiosity, there is also a diffuse structure and inflated?and sometimes hokey?prose: "In SimTown, many other things can happen including houses being set on fire and goldfish flopping out of their bowls. (I'm leaving off the quotes merely as a shorthand?I know they aren't real goldfish!)". His cheery gee-whizzery often rings false, and there's probably a good reason for the hollow sound?in 1993, his wife died of a rare disease, which probably also explains his choice of the verse. This book pays tribute to her, while illustrating the powers and limitations of speech. $60,000 ad/promo.

Copyright 1998 Reed Business Information, Inc.

The author of the famous meta-mathematical treatise G”del, Escher, Bach investigates the formal qualities of language, translation, and literature in a friendly, sometimes brilliant, but generally pedantic series of meditations. Hofstadter's hymn to language overflows with chatty narration and personal anecdotes, all revolving around a tightly formed nucleus: his efforts ten years ago to translate into English a ``sweet, old, small, elegant'' love poem by the French Renaissance writer Clement Marot. Hofstadter tells how he came to understand translation in terms of various logical models for the transferability of patterns. He illustrates these models with a tremendous hodgepodge of case studies involving literary translations but also hexagonal chess games, off-color jokes, Chopin compositions, and problems that arose in translating G”del, Escher, Bach into other languages. Hofstadter draws particularly on insights framed in his own field, artifical intelligence, where the question of translatability raises larger philosophical questions of what it means to be human. Each chapter features a version of Marot's poem or other poems by Hofstadter or one of his friends illustrating points at issue. But despite Hofstadter's multifarious ingenuity, his central insights--e.g., the sublime complexity of language--seem banal. The complexities which Hofstadter explores will for the most part seem familiar, not just to philosophers of language and literary critics, but to thoughtful lay readers. Even the idea of love that Hofstadter offers (which posits that ``each human soul is a distributed entity that is, of course, concentrated most intensely in one particular brain but that is also present in a diluted or partial manner in many other brains''), while sincere, seems densely labored. While Hofstadter deserves praise for trying to rekindle the romance between science and literature, he might have succeeded better had he recalled their long-shared history, instead of feeling called on to engineer a blind date. -- Copyright ©1997, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved.

Using a small but stylistically potent work by 16th-century French poet Clement Marot as a compass, Hofstadter (Godel, Escher, Bach, LJ 10/1/79) takes us on the sea of issues related to the act and product of translating. The reader encounters questions, such as what is translation? How does the translator cross cultures? Who can judge the validity of the translated product? When is a translation more than repackaging one vocabulary with another? Where does the reader/listener comprehend that there is an original behind the translation? He succeeds in demonstrating his subtitle as a heady metaphor of literal truth: translation is a constant human condition because "words do not have fixed imagery; context is everything." Combining autobiography, scholarly insights on artificial intelligence and a variety of human languages, a contagious sense of play, and incisive writing, Hofstadter's work deserves attention from scholars and alert layreaders. Highly recommended for academic and public library collections.?Francisca Goldsmith, Berkeley P.L., Cal.

Copyright 1997 Reed Business Information, Inc.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.