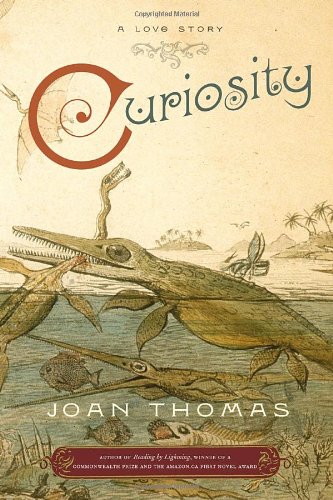

Items related to Curiosity

Synopsis

Award-winning novelist Joan Thomas blends fact and fiction, passion and science in this stunning novel set in 19th-century Lyme Regis, England — the seaside town that is the setting of both The French Lieutenant's Woman and Jane Austen's Persuasion.

More than 40 years before the publication of The Origin of Species, 12-year-old Mary Anning, a cabinet-maker's daughter, found the first intact skeleton of a prehistoric dolphin-like creature, and spent a year chipping it from the soft cliffs near Lyme Regis. This was only the first of many important discoveries made by this incredible woman, perhaps the most important paleontologist of her day.

Henry de la Beche was the son of a gentry family, owners of a slave-worked estate in Jamaica where he spent his childhood. As an adolescent back in England, he ran away from military college, and soon found himself living with his elegant, cynical mother in Lyme Regis, where he pursued his passion for drawing and painting the landscapes and fossils of the area. One morning on an expedition to see an extraordinary discovery — a giant fossil — he meets a young woman unlike anyone he has ever met...

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Joan Thomas’s debut novel, Reading By Lightning (2008), won the Commonwealth Prize for Best First Book (Canada/Caribbean) and the Amazon.ca First Novel Award. Joan has worked as a teacher, group-home worker, editor, and as the Writing and Publishing consultant at the Manitoba Arts Council. She was a books columnist and longtime contributing reviewer for the Globe and Mail, and in 1996 won a National Magazine Award (Silver) for Creative Non-Fiction. Joan's second novel, Curiosity, was published in March of this year. Joan lives in Winnipeg.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

ONE

They were powerful charms, curiosities. The people who came to Lyme Regis to take the waters would pay sixpence for the meanest little snakestone, and carry it for luck. Mary’s mother had worked the curiosity table until lately, and if a customer had trouble parting with his coin, she would fix a soft look on him and offer a charm against wizening. She was not bold in her manner and the gentleman would startle and wonder at her meaning. But usually he bought, after that.

Now that her mother had the baby to look after, the curiosity table was Mary’s job. Mary had come out early to get set up for the coach from Bath. Her wares were all organized on the table, and the square was still empty. There was just the brown hen tethered beside her, and the pauper Dick Mutch lying in stocks a few feet away in front of Cockmoile Prison. Mary sat deep in thought, her eyes on the moon, a useless, daylight moon, floating in a blue sky.

Wizening – it was a complaint particular to men. She needed a more general charm. Blindness, she finally decided. She tried it out in a low voice: “They be a powerful charm against blindness.”

She watched the moon impale itself on the steeple of the shambles, and then she bent back over her wares: Devil’s toenails, sea lilies, thunderbolts, brittle stars, verteberries, snakestones. Mary had lined them up in rows by kind. The loveliest were the snakestones, coiled serpents in gold and bronze – missing their heads, though, in their natural form. Mary’s brother Joseph had come home on his dinner break expressly to rectify this. He used a tiny stone chisel to make a pointed smile on the outer coil of each snakestone, unconsciously holding his mouth in the shape he was aiming for. Then he took up a drill to make the eyes. Six snakes had been so improved before he ’d had to pelt back up Church Street to work. On second thought, Mary slid these six out, and made a separate row for them at the front of the table.

Just as the moon freed itself from the steeple, a silver bugle sounded from the top of the hill. This was the signal for every peddler in town to pour into the square. Then there was the coach itself, plunging down Broad Street in heavy pursuit of its wild-eyed horses, and in a flash it sat, a black and gilt cage, gleaming in front of the prison. The footman had a stool at the ready and the door burst open. First out were two small dogs, touching smartly down on the footstool, and then a collection of gentlefolk, dazed by their harrowing descent and by the brouhaha of the men in the prison, who stuck their arms through the beggars’ grate and set up howling at the sight of strangers. Last off were the poor, struggling down a ladder from their perch on the roof.

In a trice, the visitors were set upon. Mary got to her feet but she did not call out. It was not in her nature to hawk, and in any case, buyers always came to the table on their own. The curiosities drew them – Mary had often experienced this power when she collected on the shore. And indeed, two ladies strolling over to look at Annie Bennett’s lavender had spied the curiosity table over Annie ’s shoulder. And then Annie lost them, they were making their way eagerly towards Mary.

“What curious stones!” said the larger of the two, picking up one of the snakestones with her gloved fingers. “What on earth are they?”

“They were living serpents one day, but Saint Hilda turned them to stone. She were clearing the earth of serpents for the protection of innocents.” As she spoke, Mary deftly turned her boot to hide the clot of mud on the hem of her skirt.

The lady wore a red and blue braided jacket, all in vogue with the high-born since the war began. As though these ladies fancied they might be called upon to fight Bony! She held the snakestone up to the light, admiring the way the snake rested its chin on the round coils of itself with a smile.

“King George himself would be proud to wear such a beauty on a sash on his belly,” Mary offered. “If he had the wits to know it.”

“If he had the wits,” cried the large lady to the other, as though a dog had made a jest, and Dick Mutch in the prison stocks (as mad as the poor king himself ) set to cackling, so that Mary must smile and say, “Pay the poor lummick no mind.” The lady set the snakestone back on the table and made to open the reticule on her arm, but her companion leaned in and said something Mary could not hear, and without another word or even a glance at Mary, the two of them went off across the square with their dogs running behind them. It was foolish to mind the discourtesies of the high-born, but Mary did mind. I should have spoke of blindness, she thought.

The square cleared, and it seemed she would have no luck at all that day, but then a man with a dirty blue bag tied to his saddle rode up on a horse. After he had gone, Mary was burning to go down to the cabinetry shop and tell her father what had transpired, but first she must pack up their wares. Sliding the curiosities onto the tray, she named them all to herself, using the queer words the stranger had used for them: the ordinary snakestones he had called ammonites, and the beautiful snakestones worked in gold and bronze, pyrite ammonites. But then, before she could go downstairs, Mrs. Stock from Sherborne Lane came bustling up to the house, and Mary must stay in the kitchen with her mother.

Mrs. Stock came inquiring after Percival, who lay like a wax doll in his cot by the cold hearth, hardly bigger than the day he was born. She was a widow with an ardent, reproachful manner that implied she would one day be more than she was, and should be heeded. She sat on the rush chair in the kitchen and darted her hungry eyes around the bare cottage as though their misfortune was secretly to her taste. Percival began to make his mewling cry. Molly picked him up and sat down in the chimney corner, opening her blouse and inching her shift down on the side away from Mrs. Stock. She spread her fingers so a leathery nipple popped out in the crotch between them, and stuffed it between Percival’s lips. He gave a tiny cry of helplessness and Molly tipped her head, resting it against his.

Mary sat on the bench and willed Mrs. Stock not to see her mother’s breast, which had been full to bursting when Percival was born and hung slack now like an empty bladder. This was down to Percival, who, for all he was an infant, had a part to play in maintaining his own keep and did not seem inclined to play it. At the end, the second Henry had been ill and thin like Percival was now, although Mary remembered him as having a queer smell to him that Percival did not have, a smell of chaff or uncured hay. The doctor came and gave him a medic, and just before he died, he coughed up two worms, both of them dead. It was the medic that killed them all three, Mary’s father said.

Mrs. Stock sat talking, talking, puffed up like a rooster with news. She had learned of a lad who had the power to heal, by virtue of being a seventh son. “The seventh son of a seventh son has the power to raise from the dead,” she explained, with the air of a teacher instructing the dim-witted. “But this boy is purely a seventh son.” The lad was only twelve, not much older than Mary, and already he ’d healed boils, dropsy, a child with a withered foot, and a woman vomiting black bile. He lived in Exeter, not so very far away.

Mary’s mother hated Mrs. Stock (she had privately said so more than once), but she couldn’t help but listen – she was a slave to the hope Mrs. Stock carried into the kitchen. They had no coals, so she sent Mary next door to the Bennetts’ to boil the kettle for tea. Mary measured out just two dippers of water so the kettle would boil quickly. When she came back, her mother was still nursing Percival and Mrs. Stock was working her way through a list of questions. She inquired as to the exact date Mary had turned eleven, as though she was hatching a plan for her. Then she turned to Lizzie, who was playing with oyster shells on the floor. “And you’re three now, my pretty one?”

Lizzie kept her head down and did not reply. “Four,” Mother said.

“And your big lad? Fourteen, I reckon? And he’s well? You had good success with the onion?” This last in a clever voice.

So then Mary saw why Mrs. Stock had come, and marvelled that she had waited this long to ask. A few weeks before, word of the pox had spread up the Dorsetshire coast, and Mrs. Stock had advised peeling an onion and hanging it from a string in the doorway to draw the pestilence to it. Mary’s mother had followed the advice, and she told Mrs. Stock so now. She had peeled the onion and hung it in the middle of the lintel. It was Richard who made her take it down – he had no use for jommetry. “He’s a history and a mystery, my Richard,” Molly said, laughing in a shamefaced way. “He will always strike his own path.”

“So I’ve heard said,” said Mrs. Stock grimly. “Well, give us a look, then.” Molly told Mary to roll up her sleeve and show Mrs. Stock the three little circles at the top of her arm. They were healed now, as dry as fairy rings in grass. “God forgive and protect us all,” Mrs. Stock cried, closing her eyes and crossing herself. “There were many who told me, but I swore it could not be true.”

It had been early morning when they first learned about the pox – Mary’s father was going out to the latrine on the bridge when a man came up from the Cobb and told him. Six dead in Bridport, he said. At first, there was excitement in the town, people standin...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMcClelland & Stewart

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 077108417X

- ISBN 13 9780771084171

- BindingHardcover

- LanguageEnglish

- Edition number1

- Number of pages416

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Search results for Curiosity

Curiosity

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00067227783

Quantity: 1 available

Curiosity

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.25. Seller Inventory # G077108417XI4N00

Quantity: 1 available

Curiosity

Seller: Russell Books, Victoria, BC, Canada

Condition: Acceptable. Dust Jacket Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # FORT814165

Quantity: 1 available

Curiosity

Seller: Russell Books, Victoria, BC, Canada

Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. Seller Inventory # FORT809570

Quantity: 1 available

Curiosity

Seller: Post Horizon Booksellers, Moose Jaw, SK, Canada

Hardcover. Condition: Near Fine. Dust Jacket Condition: Near Fine. First Canadian Edition. 409pp. Blue boards w gilt lettering to spine. No wear to covers or spine. Binding square and sound. Illustrated DJ is clean and without wear, preserved in mylar cover. Octavo. 1st printing. Seller Inventory # 048751

Quantity: 1 available

Curiosity

Seller: Werdz Quality Used Books, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. 1st Edition. INSCRIBED: FOR MARY - ALL BEST WISHES, JOAN THOMAS; Clean, tight, unmarked; several pages had the corner turned; otherwise very minimal wear; More than forty years before Darwin, Mary Anning found the fossilized skeleton of a dolphin-like creature in the cliffs of Dorset. This was only the first of many important discovers made by this exceptional woman. Anning may have been the most significant paleontologist of her day, even though her finds were taken over, named, and exhibited by the male scientific establishment - including a young man named Henry De la Beche. Inscribed by Author(s). Seller Inventory # 005317

Quantity: 1 available

Curiosity

Seller: Werdz Quality Used Books, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. 1st Edition. SIGNED BY JOAN THOMAS on title page; Clean, tight, unmarked; very minimal wear; More than forty years before Darwin, Mary Anning found the fossilized skeleton of a dolphin-like creature in the cliffs of Dorset. This was only the first of many important discovers made by this exceptional woman. Anning may have been the most significant paleontologist of her day, even though her finds were taken over, named, and exhibited by the male scientific establishment - including a young man named Henry De la Beche. Signed by Author(s). Seller Inventory # 006651

Quantity: 1 available