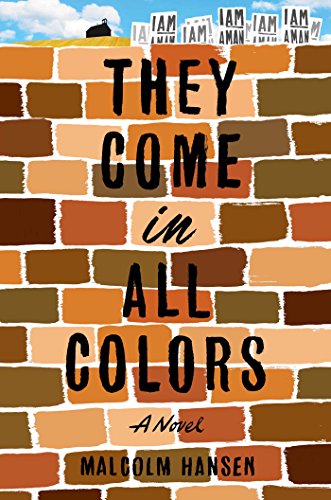

Items related to They Come in All Colors: A Novel

Synopsis

2019 First Novelist Award from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association

Malcolm Hansen arrives on the scene as a bold new literary voice with his stunning debut novel. Alternating between the Deep South and New York City during the 1960s and early '70s, They Come in All Colors follows a biracial teenage boy who finds his new life in the big city disrupted by childhood memories of the summer when racial tensions in his hometown reached a tipping point.

It's 1968 when fourteen-year-old Huey Fairchild begins high school at Claremont Prep, one of New York City’s most prestigious boys’ schools. His mother had uprooted her family from their small hometown of Akersburg, Georgia, a few years earlier, leaving behind Huey’s white father and the racial unrest that ran deeper than the Chattahoochee River.

But for our sharp-tongued protagonist, forgetting the past is easier said than done. At Claremont, where the only other nonwhite person is the janitor, Huey quickly realizes that racism can lurk beneath even the nicest school uniform. After a momentary slip of his temper, Huey finds himself on academic probation and facing legal charges. With his promising school career in limbo, he begins examining his current predicament at Claremont through the lens of his childhood memories of growing up in Akersburg during the Civil Rights Movement—and the chilling moments leading up to his and his mother's flight north.

With Huey’s head-shaking antics fueling this coming-of-age narrative, the story triumphs as a tender and honest exploration of race, identity, family, and homeland.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Malcolm Hansen was born at the Florence Crittenton Home for unwed mothers in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Adopted by two Civil Rights activists, he grew up in Morocco, Spain, Germany, and various parts of the United States. Malcolm left home as a teenager and, after two years of high school education, went to Stanford, earning a BA in philosophy. He worked for a few years in the software industry in California before setting off for what turned out to be a decade of living, working, and traveling throughout Central America, South America, and Europe. Malcolm returned to the US to complete an MFA in Fiction at Columbia University. He currently lives in New York City with his wife and two sons.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

They Come in All Colors III

EVEN IF THE BILLBOARD OUT front said that the Camelot was the perfect rest stop for snowbirds passing through Akersburg on their way to Florida, it owed its survival to the moms who brought us kids to the pool out back. Mister Abrams opened it to us kids six weeks a year. The rest of the time, it was only for his motel guests. But for those six steamy, hot weeks of summer he practically let us have the full run of the place. I ran in that day expecting to see a bunch of my friends horsing around, only to find the place empty. Dad strolled in behind me asking if anyone was here yet.

I slid the patio door open and stripped down to my trunks while Dad went on like a broken record about how nice it was to have the pool all to ourselves for a change. He eased himself in and held up his hands like he was about to catch a football. The agreement had been for me to jump in on the count of three, but on two a voice boomed out, You can’t be in there!

It was Mister Abrams. Dad hoisted himself up the stepladder and headed on over to see what was the matter. As the two of them stood there talking, I went to check out the Coke machine sitting underneath the wraparound staircase leading to the catwalk above, only before I’d even reached it, Dad shouted out for me to pack up. Pool’s closed, he said.

What’s more, he was just as tight-lipped out in the parking lot as he had been poolside. So I kept my mouth shut, like I always do when I don’t know what the heck’s going on; that is, until we pulled back onto Cordele Road.

What was that all about?

Dad started explaining about this time last year when my friend Derrick had lit a brush fire out behind his shed and his mom had called the fire department all the way up from Blakely, when she could just as well have put the damned thing out with her garden hose.

The point is . . . People overreact. Derrick probably just got caught tinkling in it, is all.

Which I knew perfectly well was true. Derrick claimed that it wasn’t so bad so long as you did it in the deep end. Being only eight and highly impressionable, I believed him. Besides, it was pretty much what all of us kids did. Which meant that Dad had no idea what the heck he was talking about.

When we got home, Mom was preparing her hot comb over the stove, and the whole house stank of bergamot. I immediately asked her if Derrick had come by.

He wasn’t at the pool? She asked the question as if Derrick being there was a given. Dad plopped himself down at the kitchen table and answered with a quick Nope.

When the comb was smoking hot, Mom hollered out to Miss Della that she was ready. Mom had been doing Miss Della’s hair since before it’d turned gray, which I’m pretty sure made her Mom’s longest-standing customer. Anyway, Dad was going on about how we’d found empty deck chairs scattered around the pool and a half-empty beach ball rolling over the terrace like a tumbleweed.

Not a soul in the place. And just as Huey’s set to hop in, Stanley comes out and tells us he’s closed. Can you believe it?

For business?

No. Just the pool.

The bathroom door opened, and Miss Della appeared in the doorway with her hair in a plastic bag and jumped right into the conversation. You didn’t hear about the two colored boys caught swimming in there last night?

I stepped back as Miss Della teetered past, the garbage bag wrapped around her neck like a four-sided apron.

Mom pulled a chair up to the sink. Trespassing?

That’s the question everybody’s asking. Why, your buddy Nestor saw them on his way home from work. From what I’ve heard, he was driving by as they were heading across Cordele Road with a shoe in each hand, and Stanley’s front office lit up like a Christmas tree. When Nestor sped up to get a closer look, they hightailed it on out of there, so scared the one didn’t bother coming back for the shoe he dropped. Nestor pulled over. And you know damned well that Nestor being Nestor, he got out of his tow truck and fetched it—then went straight to the police and handed it over, along with the story of what he’d seen.

What kind of shoe was it?

Hell if I know. But apparently the sheriff’s wondering if Stanley ain’t been letting coloreds in after hours for a small fee.

You’re kidding.

Do I look like I’m playing a practical joke?

Akersburg was a nice place to live, but like any place, we had our problems. Mostly with colored people. Anyway, Miss Della was the Orbachs’ housekeeper. Whenever I saw her around their house, it was always Yes, ma’am and No, ma’am and Right away, ma’am. But the second she stepped foot in our house, I never heard a woman cuss so much in all my life. She didn’t give a damn what Mom or Dad thought—except where it concerned her hair.

Mom eased Miss Della into a chair and sent me out to help Toby clean the points and adjust the timing. Toby had been around as long as I could remember. It didn’t matter if it was the cistern or a watch: if a man made it, Toby could fix it. I watched from the open doorway as Mom tipped Miss Della’s head back over the kitchen sink and rinsed out the blue grease. All the while, foul-mouthed old Miss Della jabbered on like a windup toy.

Toby had the hood of our truck up and was struggling to get the distributor cap off. He was cussing under his breath because he could only turn the wrench in tiny increments. I walked up behind him and coughed. Toby emerged from the engine compartment with a grateful look on his face. Getting that damn distributor hold-down bolt off was one of the few things I could help him with. My hands were small enough to give me easy access. He helped me up onto the bumper, handed me the wrench, and said for me to Have at it.

· · ·

WHEN IT GOT too dark to go on, Toby sent me inside to wash up. Miss Della was gone, and Mom and Dad were sitting at the kitchen table trying to figure out what colored man in Akersburg had gumption enough to swim in the Camelot’s pool. When I said to Dad never mind who, but why, he told me to go back outside and continue helping Toby. When I showed him the grease covering my hands, he handed me a gingersnap and told me there would be another one waiting just as soon as Toby and I finished up.

It was pitch black out. From the front window, Toby was visible under the pool of flickering patio light. He let the hood slap shut and a square of dust kicked out from under it. I let the curtain fall back over the front window. He’s done!

Then help your mother.

His lazy ass had moved into the den. From the sound of it, he was lying on his back watching The Price Is Right. Mom was sweeping crisps of hair from the kitchen floor. She asked me to start in on the dishes. A few minutes later, Toby was standing beside me. He reached over and washed his hands in the sink, then took the Pyrex that I’d been struggling to get clean, scraped off the rice caked on it, and handed it back. Toby then pulled a plate of rice and beans from the oven and limped out to the back porch.

I stood there with that dish in my hand, stunned. Dad stalked in from the TV room cursing Mister Abrams’s pool, hot weather, and Mondays. He complimented me on how clean I’d gotten the Pyrex, then asked Mom how much she’d bid on a new-model Westinghouse slow cooker. When she said eleven or twelve dollars probably, he demanded to know when in the Lord’s name that old skinflint Stanley was going to get around to cleaning that damned pool of his.

I didn’t see what the big deal was, especially considering that everyone trespassed occasionally. Sometimes there was no getting around it. You had to cut through one place to get to some other place. I had. And my buddy Derrick had, too. He bragged about it. Besides, if dirt was the issue, there were plenty of people who could take care of that, Miss Della being the first who came to mind. Missus Orbach was always boasting about how sparkling clean Miss Della got her bathroom.

I dragged a chair up to the cupboard and pulled down a milk glass. I thought that’s what chlorine was for.

That’d be like using a Band-Aid to fix a broken neck.

Mom dumped a mound of hair in the wastebasket and mused about how Mister Abrams had originally built his ramshackle motel to cater to the countrified Negros who lived on the outskirts of town back in the days of the sprawling pecan plantations. Of course, it didn’t have a pool back then.

Never mind all that, honey. The real issue here is that I paid up front for those swim lessons. Stanley asked if I wanted a receipt and I said, ‘What’s a receipt between old friends?’ Son of a bitch if that wasn’t a mistake. I want my money back.

You what?

Goddamnit, Pea. Horsing around in a pool isn’t the same thing as knowing how to swim! I figured it was a good opportunity to ask Danny if he wouldn’t mind giving Huey a few lessons. Hell. The boy was captain of the high school swim team. I thought it was a great idea. Instead of just sitting around on his rump playing lifeguard, he might as well give Huey a few pointers. The money was just to make it worth his trouble.

Mom pulled down a coffee tin from the cupboard and counted what was left. Dad winked at me and asked Mom if there was any more pie left. She pointed to the back porch and complained about him spending money we didn’t have.

Although Toby never ate with us, he usually waited in the kitchen while Mom packed up leftovers for him. When he limped past Dad on his way in, rinsed off his plate, put it away, and left by the front door, I figured he was giving me the cold shoulder for pestering him so much to let me file down the points. Even though he was always complaining about how much work it took to keep the carburetor in sound working order—taking it off every other week to adjust it—he never let me do that part. Getting the distributor cap off was one thing, but adjusting the timing was something else. He paused in the doorway and looked my way, then wiped his mouth on the back of his hand and headed out. It wasn’t much. Just a look—enough for me to know that he wasn’t sore at me.

Mom stood at the stove yapping to Dad about how he just needed rest. She suggested he put his head back down and try his hand at another catnap. Instead, he paced up and down the kitchen, eating straight out of the pie dish while complaining bitterly about how he was too tired to work and too restless to sleep, and how prices are going through the roof, and that thirteen dollars is a ridiculous amount to ask retail for a slow cooker, even if it is a Westinghouse.

Dad was starting to drive me crazy. I helped myself to that second gingersnap and ducked out the back door. About a hundred yards out, a light flickered upstairs at the Orbachs’. I propped myself up by the banister and stood on my tippy-toes to see if Derrick’s bedroom light was on; maybe he knew what the heck was going on. It wasn’t. I plopped myself down on the stoop and gazed out over the saddest-looking peanut crop you ever did see, all the while wondering what to make of all the fuss.

· · ·

THAT POOL WAS the only thing I had to look forward to for the entire month of July. It was practically the only time I got out of the house. Six days a week I’d drag my feet from bedroom to bathroom to kitchen and out onto our creaky back porch, where I’d work for most of the day. Then, come Saturday, you couldn’t find a happier kid on the planet, goofing off, making waves in that pool as I did. I kicked at the dirt and headed for the silhouette of the Orbachs’ house, the light still blinking in the distance.

The Orbachs had a one-eared mutt named Pip. Derrick said they didn’t let her inside because she was a work dog. I’d never seen her work a stitch in her life, unless you count the way she ran up to me at the fence posts that separated our fields from theirs. Pip jumped up on me, wagging her tail and sniffing and licking me all over. She pranced alongside me all the way up to Derrick’s bedroom window. I told her to keep quiet and knelt down and combed my fingers through the dirt, looking for an acorn or a pebble—anything that would reach the second-floor window without breaking it. But Pip wouldn’t let up. Frustrated with me for not playing with her, she barked. Before I was able to muzzle her, the front door opened. Missus Orbach was standing in the doorway glaring at me.

Damn you, Huey!

I bolted. Missus Orbach was on top of me before I’d even made the line of fence posts. She grabbed me by the neck and I squawked so loud birds flushed and field mice scattered. She dragged me across the field, under the clothesline, and around the side of our house. She mounted the bottommost step and banged on the front door.

Dad poked his head out.

I found him creeping around!

On account of the pool being closed, Pop! I swear it! Christ almighty, I gotta come up with something else to do on Saturdays now! Either that or get to the bottom of who did it so Mister Abrams can open it back up!

What’d I tell you about poking your nose in other people’s business, Huey?

If not me, then who? The police? The last case they cracked was. Well, Mister Nussbaum still hasn’t gotten his pig back.

Dad told me to apologize.

But my lessons! Don’t you get it? Danny packs up and goes back to college in four more weeks. No lifeguard, no swim lessons. It’s as simple as that. Mister Abrams is always saying that he doesn’t trust any of the other teenagers to look after us kids! So unless I get to the bottom of this, and quick, I may as well kiss that pool goodbye! Besides, you already paid for my damned lessons. Said so yourself. You don’t wanna lose that money, do you?

Dad apologized to Missus Orbach. He walked her down the stoop and assured her that whatever was going on with me, he’d sort it out. Missus Orbach said that I sounded like a prairie dog scurrying around in her hedgerows and that I was lucky not to have been shot, then disappeared in the darkness.

· · ·

AKERSBURG IS MORE of an administrative center for all the local farmers than an actual town. So I just assumed that it was like Dad had said: people just get riled up over the least little thing, just to have something to talk about. Gives them a sense of community. So I pretty much wrote off the matter concerning Mister Abrams’s pool, hoping that all the hubbub would blow over in a couple of days and that would be that. But after the fifth day, Mom and I were watching TV after supper when we heard a loud knock knock knock knock knock knock knock knock knock at the front door.

Mom didn’t take late appointments. She turned down the volume and went to see who it was.

Mister Abrams gave an embarrassed grin in the milky light cast from above the front door. Mom opened it further and invited him in. I shot up in my seat, hoping that he’d come to announce that whatever the heck had been going on was all better now and us kids were welcome back. He took off his hat and told her that he’d just come by to have a quick word with Dad. Mom hung his hat up and led him into the kitchen. Dad was out back repairing stack poles with Toby. She went to get him.

I slid down from Dad’s easy chair and followed Mister Abrams into the kitchen. When the storm door smacked shut behind Mom, he pulled from his ov...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAtria Books

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 1501172328

- ISBN 13 9781501172328

- BindingHardcover

- LanguageEnglish

- Edition number1

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Search results for They Come in All Colors: A Novel

They Come in All Colors

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Very Good. Seller Inventory # 00082495549

Quantity: 1 available

They Come in All Colors: A Novel

Seller: Bookmonger.Ltd, HILLSIDE, NJ, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Crease on cover and a few pages* Marks on edge *. Seller Inventory # mon0000646850

Quantity: 2 available

They Come in All Colors: A Novel

Seller: Once Upon A Time Books, Siloam Springs, AR, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Good. This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . Seller Inventory # mon0000641905

Quantity: 1 available

They Come in All Colors

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.15. Seller Inventory # G1501172328I4N10

Quantity: 1 available

They Come in All Colors : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 14981098-6

Quantity: 2 available

They Come in All Colors : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 17696868-75

Quantity: 1 available

They Come in All Colors: A Novel

Seller: GF Books, Inc., Hawthorne, CA, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Book is in Used-VeryGood condition. Pages and cover are clean and intact. Used items may not include supplementary materials such as CDs or access codes. May show signs of minor shelf wear and contain very limited notes and highlighting. 1.09. Seller Inventory # 1501172328-2-3

Quantity: 1 available

They Come in All Colors: A Novel

Seller: Craig Hokenson Bookseller, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Near Fine+. Dust Jacket Condition: Near Fine+. First Edition/First Printing. Seller Inventory # 044156

Quantity: 1 available