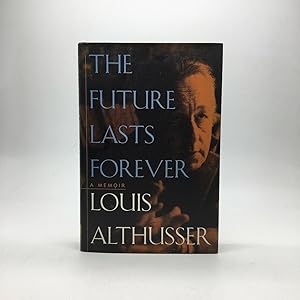

Synopsis

The Future Lasts Forever is the famous French philosopher Louis Althusser's memoir written during his years of confinement in a mental hospital after murdering his wife. Reminiscent to many readers of Strindberg's Diary of a Madman and Styron's Darkness Visible, The Future Lasts Forever is a profound yet subtle exercise in documenting madness from the inside. This paperback edition also includes Althusser's earlier autobiographical essay "The Facts," as well as a preface by Douglas Johnson, Emeritus Professor of French at London University.

Reviews

French Marxist philosopher Althusser (1918-1990) was a manic-depressive with a long history of mental instability and constant medication. In 1980 he strangled his wife Helene; the murder was officially ascribed to temporary insanity, and after two years in a mental hospital he was set free. In this strained, painful memoir, written in 1985, Althusser attempts to persuade the world of his innocence through a convoluted psychoanalytical self-analysis. He writes of his castrating, sadistic mother who was brutalized by his authoritarian father, a bank manager. We learn of the philosopher's ordeal in a German prisoner-of-war camp during WW II, of violent quarrels with Helene and an analyst, and of his suicidal depression after her death. Also included is an autobiographical sketch from 1976 which discusses his boyhood in Algiers and Marseilles and the evolution of his political thought and communist politics.

Copyright 1993 Reed Business Information, Inc.

In a curiously lucid and compelling narrative, Althusser (1918-90), a distinguished neo-Marxist French intellectual, explains his life, philosophical career, politics, recurrent depressions, and therapies--and how, on the morning of November 16, 1980, he discovered that he'd strangled H‚lŠne, his wife and companion of 30 years. Having murdered the one person he could relate to--and on whom he totally depended--Althusser was confined, in spite of public outrage, to an insane asylum, deprived by his mental condition of a public trial and defense. Was he sleepwalking when he killed H‚lŠne, as Douglas Johnson improbably claims in an introduction? Was he acting on his wife's wishes, as Althusser says at one point, or was he in an ``intense and unforeseeable state of mental confusion,'' perhaps caused by antidepressants, as he claims at another? The motive is uncertain, but about Althusser's depressions there's no confusion: As he sees it, he spent the major part of his life--spawned by a missing father and an emotionally castrating mother--fathering himself (through philosophy) and fulfilling his mother's desires. Althusser traces a bizarre emotional choreography of alternating compliance and rebellion, seeing his immensely influential philosophy as a working out of childhood problems, with a subsequent fear of exposure as a fraud. He met H‚lŠne, eight years his senior, when he was nearly 30, and recently released from German prison camp. She became the first woman he would ever kiss, initiating a tumultuous sado-masochistic relationship between them. Meanwhile, leading French thinkers--Foucault, Lacan, Derrida- -briefly appear in the text, but Althusser, insulated by his self- preoccupation and misery, reveals little about them or the intellectual ferment of his times. A disturbing, demanding memoir that illustrates the alliance of genius and madness, the delusive clarity of which the insane are capable, and the enormous influence they can acquire over the thinking of others. -- Copyright ©1993, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved.

Althusser (1918-90) made a minor mark in 20th-century French intellectual history with his teachings on Marxism. Outside the academy, he may be better known as the professor who murdered his wife and then spent time in the insane asylum rather than standing trial. The current volume brings together two pieces that are personal rather than philosophical: "The Future Lasts a Long Time" was written some years after his wife's death in 1980 but reaches back to detail Althusser's childhood and adolescence; "The Facts," written in 1976, covers that distant past more quickly and pithily. While these two memoirs are well presented, and the former does provide an interesting view of the murder, this publication does nothing to advance philosophical scholarship. Casual readers of contemporary biography may be interested.

- Francisca Goldsmith, Berkeley P.L., Cal.

Copyright 1994 Reed Business Information, Inc.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.